Introduction

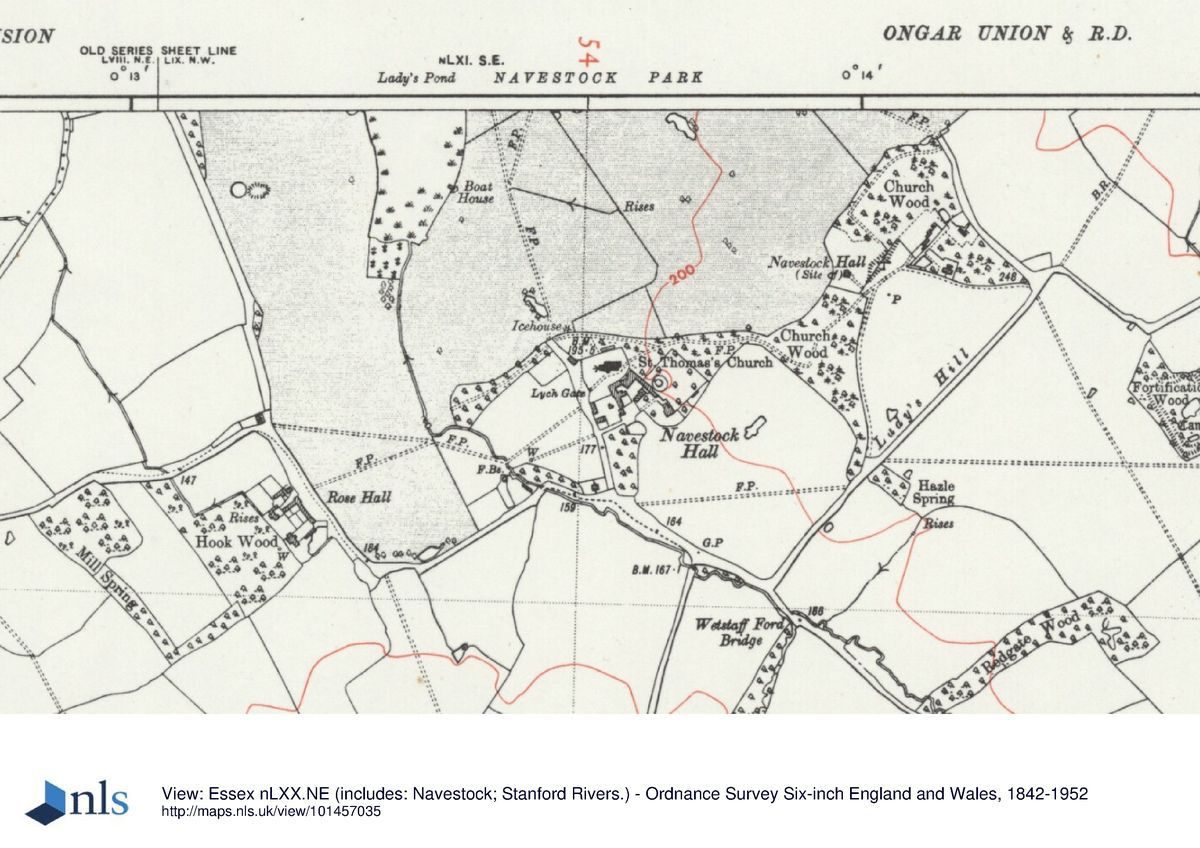

More than a century after its abandonment, many of the features of the park and pleasure grounds can still be identified. The area of the pleasure grounds, its sunken fence and walled vegetable garden remains unaltered, though now very overgrown in parts. The park is under arable cultivation but the majority of the peripheral woodland has survived.

More than a century after its abandonment, many of the features of the park and pleasure grounds can still be identified. The area of the pleasure grounds, its sunken fence and walled vegetable garden remains unaltered, though now very overgrown in parts. The park is under arable cultivation but the majority of the peripheral woodland has survived, albeit some replanted with conifers. The narrow strip of woodland linking Aspen Wood to Hollingford Spring has been removed, presumably to facilitate cultivation, but much of Brown's carriage drive can still be followed on foot. The lake has been maintained for coarse fishing, with modern sheet pile repairs to part of the dam, as well as repairs in concrete to Brown's original overflow, and the provision of a new outlet at the north end.

Sources

Anon, 1771 Gentleman's History of Essex, iv, 48, Chelmsford

Dubois Landscape Survey of Navestock Park for English Heritage, June 1995, typescript

Essex Quarter Sessions bridge repair presentments 1580, 1586, 1617, 1641 & 1677 ERO Q/SR 73/62, 98/19, 218/29-30, 314/62 & 436/36

Highway diversion order 1766 ERO Q/RHi 2/8

Plan of the manor of Navestock 1726 ERO D/DZn 3

Survey of the manor of Navestock 1615 ERO D/DU 583/1

Manor and parish of Navestock 1785, updated to 1835 ERO D/DXa/24

Registration of Papist estates 1717 ERO Q/QRp 1/51

Lewis, W.S. (ed.), 1970 Horace Walpole's Correspondence, ix, 243, Yale University Press

Sharp, P.D.R., & Leach, M., 2011 ‘Fortification Wood, Navestock - Reviewed' in Transactions of Essex Society for Archaeology & History, 4th series, ii

Stroud, D., 1975 Capability Brown, Faber & Faber

Turner, R., 1985 Capability Brown and the 18th Century English Landscape, Rizzoli

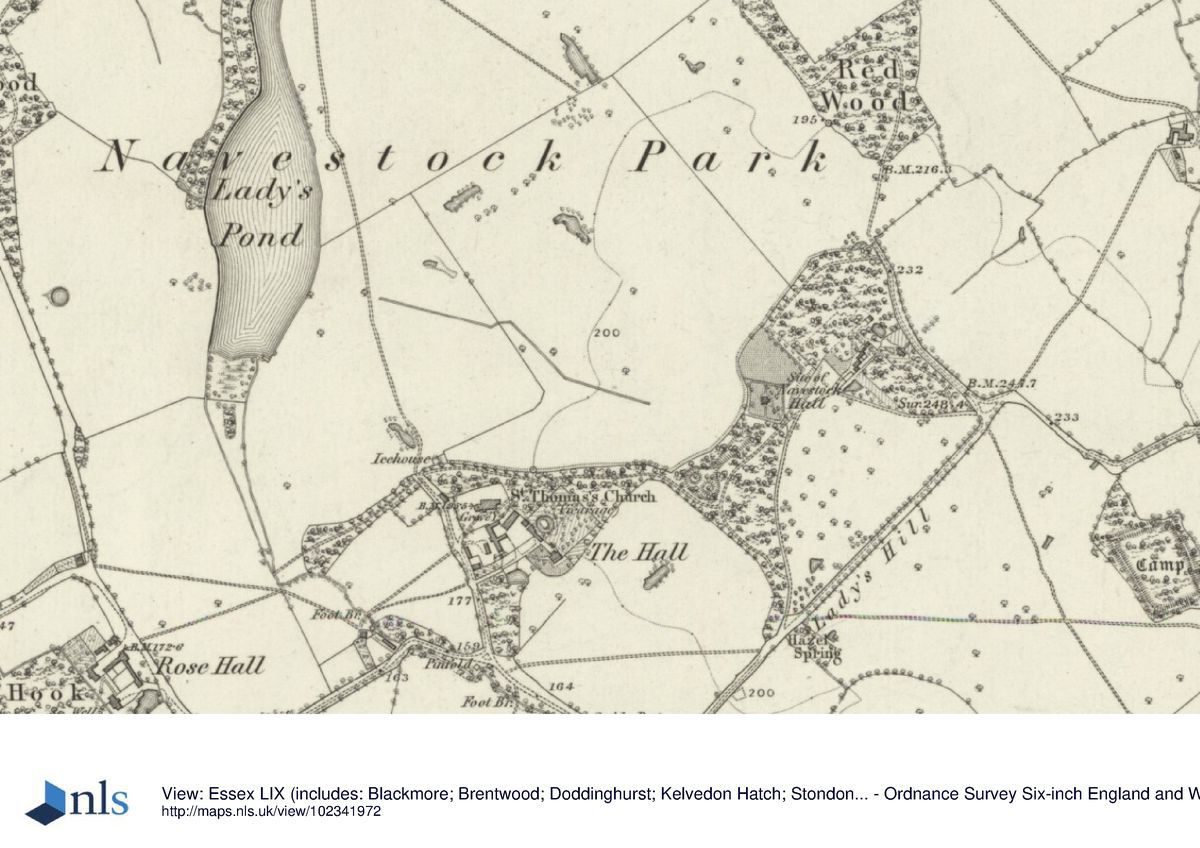

OS 6" 1870-3 sheets 58 & 59

Chapman & André map of Essex 1777

Lancelot Brown's account book, Lindley Library (transcribed by Stephie Shields)

Detailed description contributed by Essex Gardens Trust 05/07/2016

- History

The improvements to the park and pleasure grounds of Navestock Hall were one of Lancelot Brown's larger projects. Though his total bill was only a quarter of that for Blenheim Palace, allowance must be made for the Essex park covering a very much smaller area than the one in Oxfordshire. Brown's work at Navestock was spread over nearly 20 years and, though the park was abandoned a few decades after its completion, there is plenty of field evidence and an invaluable series of maps which show the earlier landscape, and how Brown adapted it. This study, based on maps, archives and printed sources, as well as a detailed field visit by the author in 2002, will look at the early-17th-century tenanted manor farm with its large demesne fields and woodland, and its adaptation in the early-18th century to provide a small park and pleasure grounds for the newly-built mansion of the first earl Waldegrave. It will then examine the alterations and enlargements made by Brown for the third earl, and the subsequent fate of the park and pleasure grounds after the demolition of the mansion in 1811.

The landform

The medieval manor house was, and still is, adjacent the church, as is usual in Essex. To the west and north, the land falls away to provide good views of the Roding valley, whose river forms a natural boundary to both parish and manor. To the south and east the land is attractively undulating but does not provide distant vistas. To the west, between the manor house and the river valley, a small stream runs northwards, roughly parallel to the Roding, before joining the main river. It was this stream (‘the little Rivulet') that was used by Brown to create a large lake.

The manorial landscape in 1615

The Waldegrave family had scattered estates in Essex, Somerset and elsewhere. Though they had owned the manor of Navestock since 1554, they did not reside here. The manor house near the church (then and now called Navestock Hall) would have been occupied by a bailiff or tenant farmer, and the whole estate would have been regarded as an investment and a source of income.

The manorial landscape consisted of a number of large fields near the manor house which were in the hands of the lord - the demesne fields - surrounded by smaller fields which were let to tenants. A plan of Navestock manor of 1615 illustrates this in some detail (ERO D/DU 583/1). Adjoining the manor house to the north and east were Broad Field (57 acres) and Long Field (37 acres); these were probably two of the demesne fields and they were to form the nucleus of the future park and pleasure grounds. To the north, the fields were interspersed with large clumps of woodland (Broom Wood, Aspett/Apsey/ Aspen Wood, Hollingford Spring and Red Wood), much of which Brown was to utilise a century and a half later to form the peripheral tree belts surrounding the park. Parts of the estate, particular the Hollingford fields, had thickly wooded field boundaries which are recognised as probable ‘post Black Death set-aside' (John Hunter, pers. com). The problems caused by surplus land and a reduced work force after the mid-15th century were solved by planting woods and springs, and by allowing hedges to thicken to form linear strips of woodland between fields. Thus the consequences of a catastrophic medieval epidemic were to provide opportunities for a landscape designer three centuries later.

Apart from a small triangular southern extension, Broom Wood remains a very similar shape today, and retains part of its medieval woodbank. It still consists largely of coppiced hornbeam. Aspen Wood, though now swamped with coniferous planting, also has surviving woodbanks and hornbeam coppice stools, as does the most south-easterly piece of woodland called Red Wood. In recent times Hollingford has been planted with conifers, though some native hardwoods are to be found here too, together with sycamore and a few horse chestnuts.

One striking difference from the present is the road system. No road is shown to the west, linking the manor to Shonks mill and the Ongar road, though a horse bridge over the river by the mill certainly existed by this date (ERO Q/SR 218/29-30 & 314/62). The main route from Navestock to Ongar ran northwards along the north-east boundary of the manor, crossing the River Roding just north of Aspen Wood at Hollingford bridge (ERO Q/SR 436/36). For wheeled traffic, this provided a more direct route to Ongar than the modern road system. It also formed the eastern boundary of the first park but was to be erased by Brown's later enlargement. No trace of this road, or Hollingford bridge, is visible today.

New mansion and park of around 1720

The Waldegraves, being a Catholic family, were excluded from all public offices on account of their religion. After the accession of the Hanoverian monarch, George I, it became clear that there was no likelihood of a tolerant policy towards Catholics and those with ambitions for a career in public life were obliged to abjure their faith. Baron James Waldegrave (1684-1741), later created the first earl, was one of these. He had grown up, and been educated as a Catholic in France, but declared himself a protestant in 1722, took his seat in the House of Lords and rapidly advanced his diplomatic career (ODNB). It seems likely that the construction of his new mansion and park at Navestock, conveniently close to London, was part of the strategy to further his political career.

The exact date of the first earl's Navestock project is not known but there is evidence that new house had been built by 1717 when the registration of Papist estates (ERO Q/RRp 1/51) refers to a ‘mansion house'. Though various fields and woods in his ownership are named, Broad Field and Great Hollingford are not, confirming that these fields had already been converted to parkland and pleasure grounds. The registration of 1717 also contains a separate reference to Navestock Hall (i.e. the medieval manor house) which was leased to a tenant. It seems probable that the entire project had been completed before 1725 as, from that date till his death, the first earl spent most of his time in overseas postings, leaving his agent, James Underhill, to run the estate. The mansion was a nine bay brick building, two storeys high above a half basement, with a three bay single storey extension at each end with a balustraded parapet. By the 1770s there was a shallow pediment over the central three bays. This is not shown on the miniature elevation on the 1726 plan but it is not clear if this had been omitted by the map maker, or was an improvement added at a later date. A semi- basement ran the full length of the building. There are no later images of the mansion and nothing else to show if the house was altered in any way while Brown was improving the park and pleasure grounds. The demolition of 1811 was very thorough and nothing remains today, other than a shallow depression marking the footprint of the basement.

The new mansion was on a virgin site on higher ground to the north-east of the manor house. The back of the house had a commanding view to the north-west down to the Roding valley, and this was where the pleasure ground, and the park beyond, were laid out. The plan of 1726 (ERO D/DZn 3) shows that main feature of the park was the double planted avenue which stretched for about 2 kilometres from the mansion to the Ongar road on the far side of the valley. Though not shown, there was already a public footbridge at or near the point where the avenue crossed the river (ERO Q/SR 98/19). This part of the line of the avenue is still a public footpath. It is not known what trees were planted, but if the first earl was keen to demonstrate his loyalty to the Hanoverian dynasty, they would probably have been limes.

The park itself was formed by combining Broad Field with Great, Lower and Upper Hollingford Fields. The thickly wooded field boundaries of the Hollingfords were considerably thinned but are still discernible on the 1726 plan. There were (and still are) two differently aligned oval pits on what had been the boundary between Broad Field and the Hollingfords. These have been described as decoy ponds, but they seem quite unsuited for this purpose. They may have been marl pits left over from earlier agricultural activity and might have been retained to provide water for grazing parkland animals.

No other obvious parkland features are shown on the 1726 plan but there had been a number of changes in the surrounding fields, the larger of which had been sub-divided. The north-western part of Aspen wood had been cleared and the resulting field given the appropriate name of Stubbs Meadow. The south-eastern corner of this wood was cut into two parts by the grand avenue, the smaller truncated piece being named Little Aspen Wood. The other significant change is the creation of a new highway to Shonks Mill where (as already mentioned) there had only been a horse bridge across the river. This new road necessitated the division of Bridge Field into two and the removal of the thickly wooded boundary on its western edge. More than a century later, this road was still marked as the ‘New Road' on an estate map (ERO D/DXa/24).

It would have provided a more direct route to London for carriages. The road to Ongar, along the north-eastern edge of the new park, remained in use.

The most striking addition to the 1726 plan was the mansion and its surrounding pleasure ground. As the original is in poor condition, sketch plans are provided here to show the main details of both. To the north-east of the house, there was a bowling green, and a new and old ‘orange walk' on each side of a ‘dwarf and fruit garden'. A single huge lime tree has survived in this area, and may be the last remnant of one of the orange walks. Nothing else can be discerned in the overwhelming scrub in this area, apart from a raised knoll on the parkland edge, planted with three yew trees. It seems probable that this feature dates from the original design, rather than a later improvement by Brown, though it is not shown on the 1726 plan. It would have provided a viewpoint overlooking the park, planted with a yew hedge to act as a wind break or to screen it from the nearby public road to Ongar.

The stables and service buildings, and the vegetable garden were placed immediately east of the mansion. The plan shows three unidentified buildings here but it provides no details of how this area was laid out. There was direct access to the main court in front of the house through a pair of gates.

To the south-west of the house a long canal was laid out, with a square hammerhead containing two islands at its southern end. Yew planting survives on one of the islands as well as at the northern end of the canal. The plan suggests that the pleasure grounds to the south-east and north-west of the canal were laid out formally with regularly planted trees, paths and parterres.

A gate led off Lady's Hill into the grand entrance court in front of the mansion. It is not clear if it was enclosed by a hedge, a fence or a wall, but it was lined with a double row of trees on each side, and had separate gates into the parterre and vegetable gardens. The area north-west of the mansion was also flanked with double rows of trees, and laid out with two long rectangular ‘beds' with scalloped corners.

Lancelot Brown's improvements

The first earl died in 1741 and there is no evidence that his successor (also James), who died in 1763, made any significant alterations. When Horace Walpole visited in July 1759 he admired the view but little else, noting ‘it is a dull place, though it does not want prospect backwards. The garden is small, consisting of two small French allées of old limes that are comfortable, two groves that are not so, and a green canal' (Lewis 1970, ix, 243).

James' brother John (1718-84) became the third earl in 1763. He had served overseas with distinction in the army but, after his succession, he obtained various honorific posts at home, both at court and in the army. Early in his ownership, he acquired the manor of Bois Hall, immediately to the north and east of Navestock Hall, and this provided an opportunity for enlarging the park. The third earl must have commissioned Brown soon after his brother's death, as he paid the first bill in October 1765, and continued to make substantial payments in most of the subsequent years up to July 1773 (Lancelot Brown's account book, Lindley Library, pp.43-4). Though it is possible to identify most of the work carried out by Brown, it is difficult to date or to sequence the improvements that he made. His largest project, Lady's Pond, is shown on the Chapman and André county map which was probably surveyed in 1773-4, though not published till 1777. The total expenditure, just over £4500, was substantial, particularly if compared with Blenheim Palace where Brown's costs, on a very much larger project, were about £21,000. The park at Navestock was never much larger than 150 acres.

None of Brown's correspondence or his plans relating to the Navestock improvements have been found. The only additional clue in the accounts is a payment of £29-7-3d for Messrs Williamson & Co's nursery bill. However a survey of the Waldegrave estate made in ‘1785 by Richard Horwood, revised and corrected up to 1835 by Richard Peyton' has survived and this provides much cartographic evidence for the changes that Brown brought about (ERO D/Dxa/24).

Highway diversion

One early improvement can be dated by a highway diversion order of 1766 (ERO Q/RHi 2/8). This abolished the public road to Ongar which ran along the north-eastern edge of the old park. The main benefit of this diversion was to enable Brown to enlarge the park to the north-east in order to widen the prospect from the mansion, and to provide a private carriage drive through the existing woodlands on the new boundary. There may also have been a desire to remove the public road to provide greater privacy for the park. The new diverted road was constructed on a straight line further east, over the brow of the slope and is well out of sight of the park. It is still in use as a farm track to the site of Slades, and on to Beacon Hill. The diversion order for the northern part of the road northwards to Hollingford bridge cannot be traced and there is no visible trace of it on the landscape.

The road to the east of the mansion, Lady's Hill, was straightened and moved a little to the south-east but no attempt was made to conceal it from the house by lowering it or by screening with woodland. A conspicuous view of the mansion from the public road must have been intended. It was also provided with a milestone giving the mileage from Whitechapel; there was another one mile nearer London on the road to Shonks Mill.

Construction of the lake

The most costly item at Navestock would have been the construction of the lake, known as Lady's Pond. This was formed by damming the little Rivulet. However, creating this impressive body of water, which would be clearly visible from the house and pleasure ground, was far from a straightforward task, as the valley of this little stream was shallow and not aligned with the axis of the planned lake. Brown solved this problem by creating a substantial embankment running the entire length of the new lake, as well as a dam at its northern end. This earthwork is about ½ km long and up to 6m in height at its midway point where it crosses the former valley of the little Rivulet.

The original overflow is about half way along its length. The spillway from the lake is now concreted, but empties into two red brick tunnels which pierce the embankment to run into a relief channel along the foot of the embankment. There are curved abutment walls (now in a poor state of repair) on the landward side and the overflow cascades over the remains of a boulder-floored riffle. Before the creation of the lake, the Rivulet originally continued some distance to the north to join the River Roding, but Brown diverted it to the west into a shorter and more direct cut. This may have been done to increase the flow rate of the overspill from the lake, and thereby to reduce the risk of flooding and erosion at the bottom of his new embankment. Near the overflow, part of the bank has failed (or has threatened to do so) in recent times and has been repaired with sheet piles.

An enormous volume of earth would have been required for the construction of such a large bank. It is unlikely that adequate quantities would have been obtained from the floor of the new lake and much must have been obtained from elsewhere. One possible source is a deep linear excavation, now densely overgrown, cut into the slope just to the north of Fortification Wood, as well as shallower excavations in the adjoining woodlands. Nearer to hand, a better view of the water from the house was provided by a shallow depression running east/west towards its southern end of the lake, still faintly visible in the ploughed field. It is not clear if this was natural feature exploited by Brown or one created by him; if the latter, it would have provided another useful (and conveniently close) source of material.

Today, the southern part of Lady's Pond has silted up but a former island, planted with two horse chestnut trees, can still be discerned. The 1871 6" Ordnance Survey map shows that this part of the lake had already disappeared, presumably the result of the limited flow of the little Rivulet that fed it. The island at the northern end of the lake has gone and there is an additional overflow at this end. It is of modern construction in concrete and blockwork, and is probably a later modification. Trees from the adjoining woodland have colonised the entire length of the embankment, but a few horse chestnuts and a regular-looking line of hornbeams may have been planted.

The peripheral woodland belts

Brown was able to use much of the existing woodland to form peripheral tree belts to enclose the park. The following description starts at the north-east corner of the pleasure ground and moves in an anti-clockwise direction.

There are no early maps showing the area which Brown used to enlarge the park to the north-east but it is clear that Red Wood, which retains part of a substantial wood bank and much coppiced hornbeam, was already well established. It appears that he linked this to Hollingford Spring with a narrow belt of oak and sycamore planting. Hollingford Spring itself has wood banks unrelated to the carriage drive, and contains some hornbeam and oak and a few horse chestnut trees. It is probably a mix of old and planted woodland. It in turn was connected to Aspen Wood by a very narrow dogleg of trees; this was cleared after World War 2 and it is not possible to say if it was planted by Brown, or carved out of the thickened field boundaries which have already been described. Aspen Wood, though now planted with conifer, contains coppiced hornbeam on its southern wood bank and its overall shape was not altered by Brown.

The lake is now reached. Part of Little Aspen Wood may have been retained but the long embankment of the lake would have destroyed some of it. The embankment itself is now covered in native trees which may have been planted to stabilise it as well as to provide a backdrop for the expanse of water when viewed from the mansion. A thin band of ash and sycamore connects the head of the lake with Broom Wood which contains coppiced hornbeam with evidence of wood banks. A triangle of woodland was added by Brown to the southern end of Broom Wood, and this was planted mainly with oak.

The carriage drive

This ran through the peripheral woodland around the circumference of the park. From the north-east side of the park it may have followed the line of the old Ongar road which had been abolished by the parkland extension. In total, four 12 foot wide red brick arch bridges without parapets were made to carry the drive over small streams during its circumnavigation of the park. The absence of a bridge over the present overflow channel from the northern end of the lake suggests that this outlet is a more recent arrangement. To the south of Broom Wood the drive probably ran on the line of the present farm track through open cultivated fields. Was this to enable the third earl to show off some of the fields of the home farm?

A faint circular depression, shown on some maps, is just discernible to the east of the drive over the open field; it is not clear if this is the remains of an eye catcher, or an agricultural artefact such as a marl pit. Having crossed the field, the drive then turned east to cross another broad bridge near the head of the lake to a short avenue of London plane. Its route back to the mansion from this point is not apparent.

Removal of the avenue

The grand double planted avenue of the first park layout, running from the rear of the mansion to the Stanford Rivers road was completely removed. It disappeared some time between 1726 (when it would have been less than 10 years old) and 1772-3 when Chapman & Andre surveyed for their map (printed in 1777). It can be stated with certainty that the avenue had gone within 7 or 8 years of Brown commencing his work at Navestock, but there is no definite evidence that he initiated its destruction.

Extension of the park to the east

The main park was broadened to the north-east, necessitating the highway diversion already mentioned. This would have provided a wider arc of view from the mansion and the pre-existing Red Wood and Hollingford Spring formed a convenient woodland screen here. In addition, a new area of park was created on the other side of the road (Lady's Hill) to the south-east of the mansion, on land which the third earl had acquired as part of the manor of Bois Hall.

The absence of earlier maps for this area makes it difficult to determine what Brown did here, though it is evident that he planted (or adapted from existing woodland) peripheral tree belts, though these, unlike the ones in the main park, did not contain a carriage drive.

One of the existing pieces of woodland was the enigmatic Fortification Wood which was extended north-westwards to meet the road. The wood contains an embanked medieval manorial enclosure and it is possible that Brown made a feature of this by cutting a deep rectangular pond within the earthworks (Sharp & Leach). The name of the wood appears to be a late-18th century or early-19th century creation.

Though Brown probably removed the grand avenue in the main park, he planted a small less formal avenue running east/west though this new area of park. Nothing of this has survived in the modern arable landscape.

Relocation of the vegetable garden

The original site was on the north-east side of the front grand court. There is now a walled garden close to the old manor house and the church, enclosed with a red brick wall in English bond, about 2 metres high. It has not been possible to examine this from the inside to establish the position of glasshouses and other facilities. It contained a circular feature which was probably a dipping pond.

It is possible that this was part of Brown's plan to remove the productive garden from the vicinity of the house. However Susan Campbell has suggested that the rectangular enclosure with a rounded north-east end, close to the mansion (and shown on the 1835 estate map) was also Brown's vegetable garden. There are Brownian precedents for apsidal ends, as well as two separate productive areas; in this instance the one near to the house may have been used for more ornamental or exotic vegetables and flowers, with the walled garden near the old manor house (a tenanted farm by that date) providing the more basic vegetables.

Just to the north-west of the churchyard an icehouse was constructed on the edge of Brown's sunken fence. The date of its construction is not known; it is built of stock brick and was probably built only a decade or two before the demolition of the mansion. It is listed Grade II.

Reorganisation of the pleasure ground

A sketch plan is provided (to the same scale as the earlier sketch plan) to show the alterations effected by Brown. He swept away the formal rectilinear layout and extended the original pleasure grounds to the south-west to link with the new walled garden and the churchyard. The groups of horse chestnuts, planted in fours, were probably part of his planting on this narrow curving extension. It seems likely that the sunken fence which separates the full length of the curved edge of the pleasure grounds from the park was part of his improvement. This boundary had been dead straight in the original layout, presumably fenced or hedged to exclude parkland animals.

Two centuries of abandonment to nature make it difficult to establish exactly what alterations Brown made to the pleasure grounds. The area occupied by the orange walks and dwarf fruit gardens appears, from the 1836 map, to have been converted to an open space edged with paths, but the entrance court, vegetable garden, stables and formal parterres were swept away to form a large semi-circular meadow or lawn between the mansion and Lady's Hill. The road itself was straightened and is now hedged with hawthorn on both sides. Surprisingly the formal canal, with its hammerhead and islands, was retained, albeit with the right-angled corners rounded off. Perhaps the third earl had somewhat old-fashioned tastes and wished to retain something of the old garden. Some yew planting on one of the islands, and at the east end of the canal, may be Brown's or from the earlier period. The raised knoll overlooking the park, planted with yew, also survived and would surely have been regarded as an old-fashioned feature by the 1760s.

However it seems that Brown's usual approach to ‘framing' the mansion with evergreens was carried out, as an evergreen oak and a yew have survived on the edge of the mansion site. To the south-west the new walled vegetable garden may have been screened with the holly and Portuguese laurel which still survive in the undergrowth here. Other possible Brown plantings in the vicinity of the house are Cedar of Lebanon and London plane.

Decline and return to agricultural use

In 1811 there was an extremely thorough demolition of the mansion, its ancillary buildings and its hard garden features, and the parkland returned to agricultural use. However this was not the end of the Waldegrave family's interest in the site as the nearby house at Dudbrook continued to be used by the family, and countess Frances Waldegrave retained a particular affection for the pleasure grounds. These must have received some form of maintenance, perhaps by the Dudbrook gardeners. She had a summer house built here and was a regular visitor until her death in July 1879. The summer house itself survived until at least the summer of 1894 when members of the Essex Field Club were provided with a ‘sumptuous luncheon' here. After the death of the countess, a monument was erected nearby by her surviving (fourth) husband, Lord Carlingford. It survives in the undergrowth and bears a portrait medallion of the countess and an inscription. This is now impossible to decipher but once read:

"This summer house standing close to the site of Navestock Hall, taken down in 1811, was built in the year 1855 by Frances Countess Waldegrave. She loved this spot to the end of her life, and left it sorrowfully not knowing that it was for the last time, on the evening of the seventeenth of June 1879" (Keith Gardner, pers. Com.).

Detailed history contributed by Essex Gardens Trust 05/07/2016

Period

- 18th Century (1701 to 1800)

- Late 18th Century (1767 to 1800)

- Associated People

- Features & Designations

Features

- Kitchen Garden

- Description: The walled vegetable garden remains unaltered, though now very overgrown in parts.

- Tree Belt

- Description: The majority of the peripheral woodland has survived, albeit some replanted with conifers.

- Drive

- Description: Much of Brown’s carriage drive can still be followed on foot.

- Lake

- Description: The lake has been maintained for coarse fishing, with modern sheet pile repairs to part of the dam.

- Key Information

Type

Park

Purpose

Agriculture And Subsistence

Principal Building

Agriculture And Subsistence

Period

18th Century (1701 to 1800)

Survival

Part: standing remains

Civil Parish

Navestock

- References

References

- Stroud, Dorothy {Capability Brown} (Faber, 1975) Capability Brown

- Turner, Roger {Capability Brown and the Eighteenth Century English Landscape} (London: Weidenfield and Nicholson, 1985) Capability Brown and the Eighteenth Century English Landscape

Contributors

Michael Leach

Essex Gardens Trust