Introduction

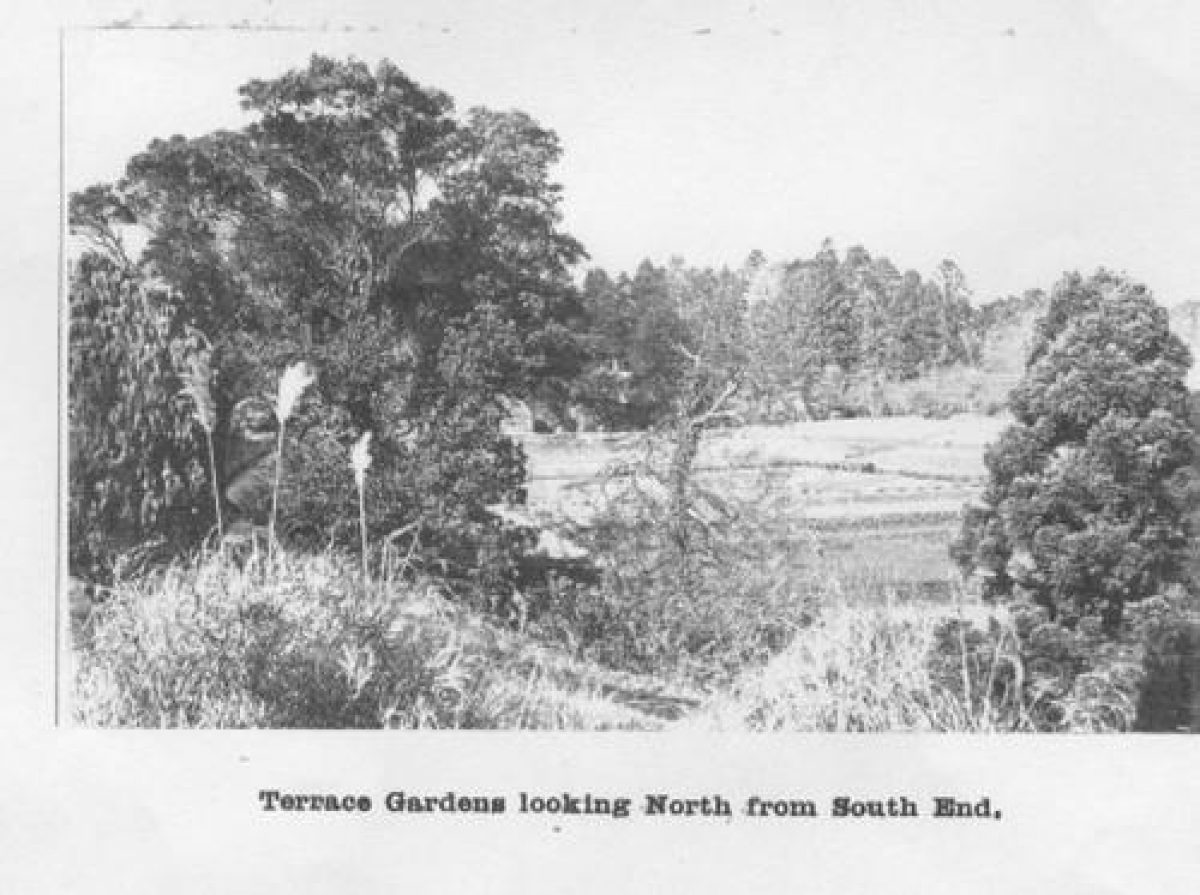

Lady Dorothy Nevill laid out the site in the 1850s. Tons of earth were imported to level a small valley to the east of the walled garden for growing more vegetables and fruit. Terrace walks and winding broad gravelled paths took the visitor around the garden. To the west of the house was a parterre and an extensive pinetum. To the east a path known as Lady Dorothy's Walk led through a wood.

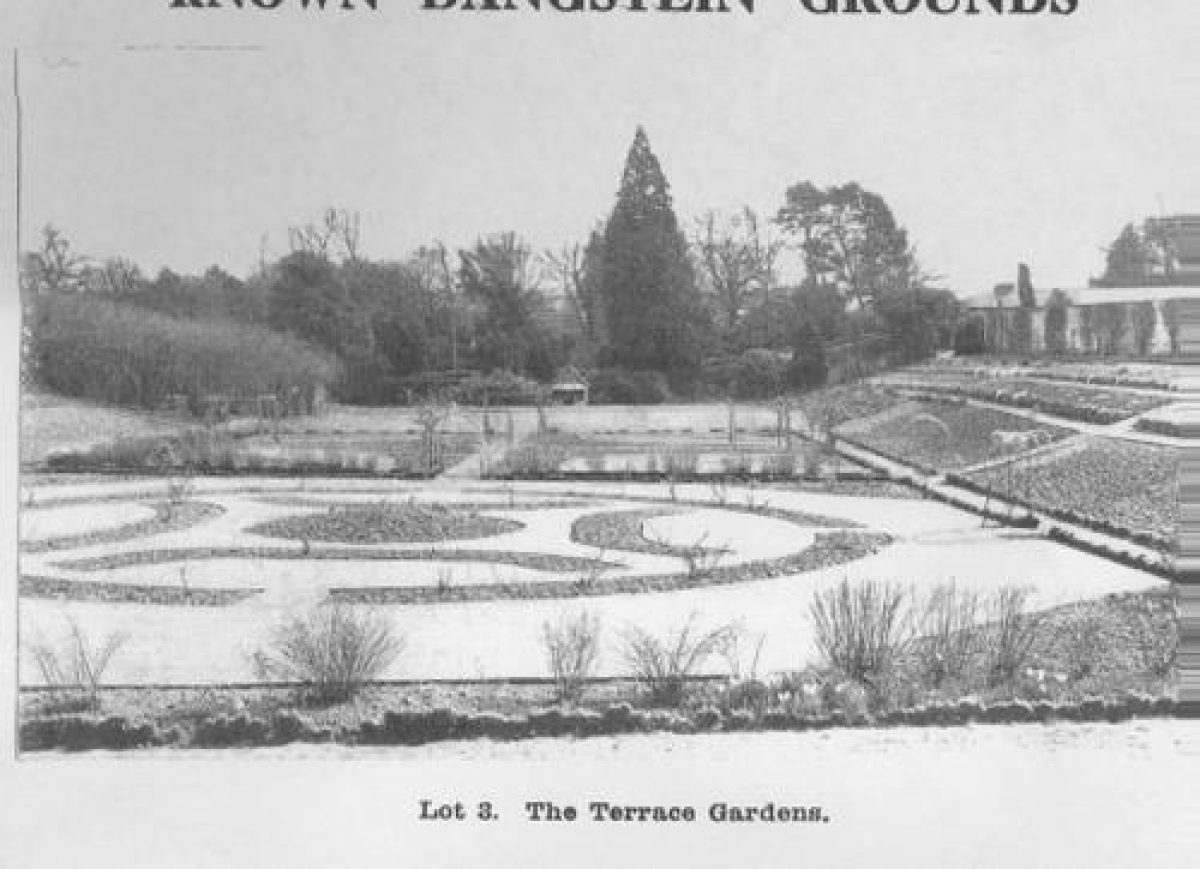

There were two walled kitchen gardens and a range of hot and orchid houses, three vineries, two orchid houses and a Peach House, a double Aviary, Pheasantry in two compartments and two pigeon lofts over a small Aviary. The estate was purchased by a solicitor, Charles Lane, who demolished some of the glasshouses and created a parterre in the partly leveled valley.

The 1919 sale particulars show that the estate had reduced in size a little, to 1425 acres and state that the grounds are finely timbered with specimen trees and rare shrubs. The house was approached by two drives with a lodge at the entrance.

Woodlands, plantations and rough undulating land formed a valued game preserve, its extent being 308 hectares (800 acres). The lake at Harting Coombe provided wildfowl shooting and fishing, with views to Goodwood.

Gardens around the house consisted of a wide terrace walk to the pinetum, with lawns to the south and west of the house. There were woodland walks, a rose garden with sloping banks, and a wild garden. The productive kitchen garden contained wall and standard fruits, and an ample range of glasshouses still remained, with a vinery, peach house and greenhouse. The fernery, Palm House, Cucumber and Melon Pits also still stood together with the normal buildings required to support a large garden.

- Visitor Access, Directions & Contacts

- History

When Reginald Nevill bought the Dangstein estate of 2000 acres in 1851, he could have had little idea that his wife would become a leading horticulturalist in her own right. Lady Dorothy was born in 1826 and was the daughter of the third Earl of Orford. She was an energetic and vibrant personality, constantly thinking up new plans both for the gardens and the people who worked there.

Her life is well recorded in various books of reminiscences together with three biographies. Contemporary articles appeared in the gardening press that showed further light on the extraordinary collection of plants that were gathered in the glasshouses of Dangstein. W R (Bob) Trotter has written in great detail of the history of the glasshouses at Dangstein and Lady Dorothy's collections of plants. This comprehensive article appeared in the Garden History Journal, Volume 16, number 1,Spring 1988.

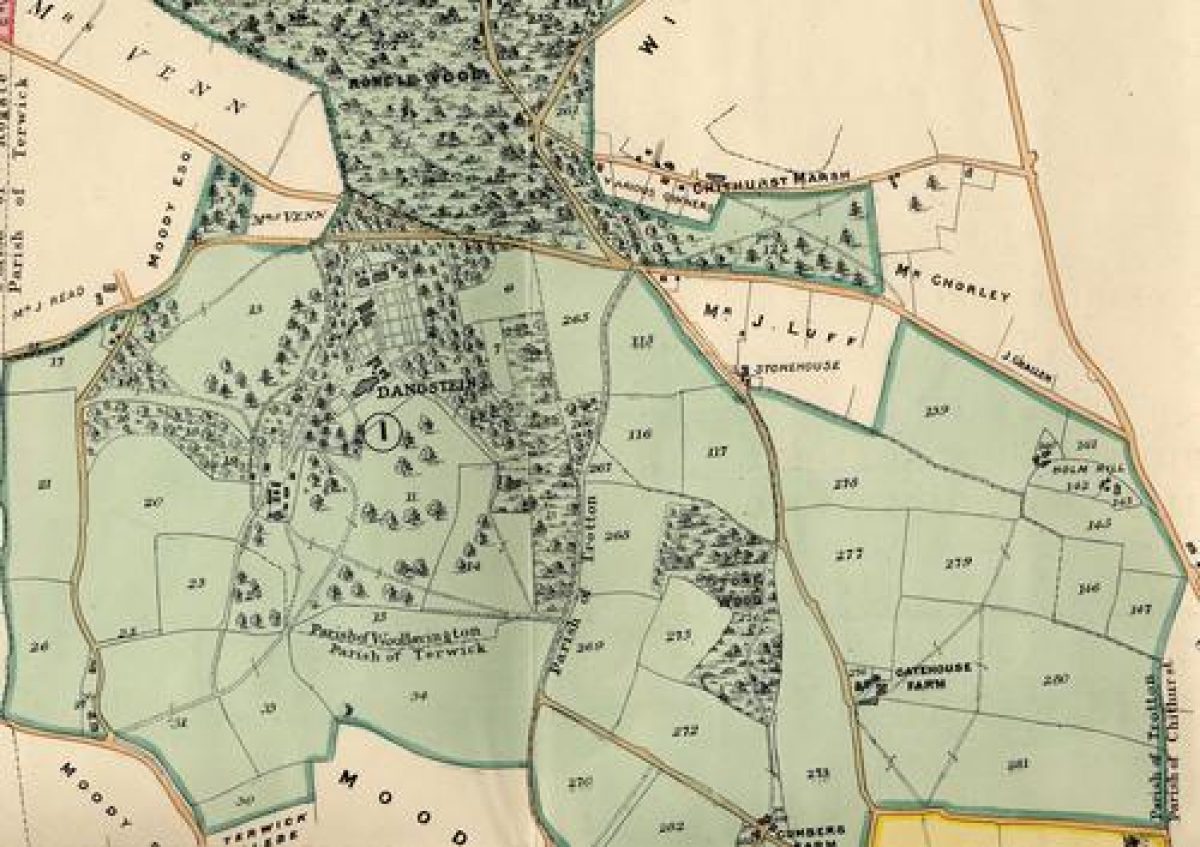

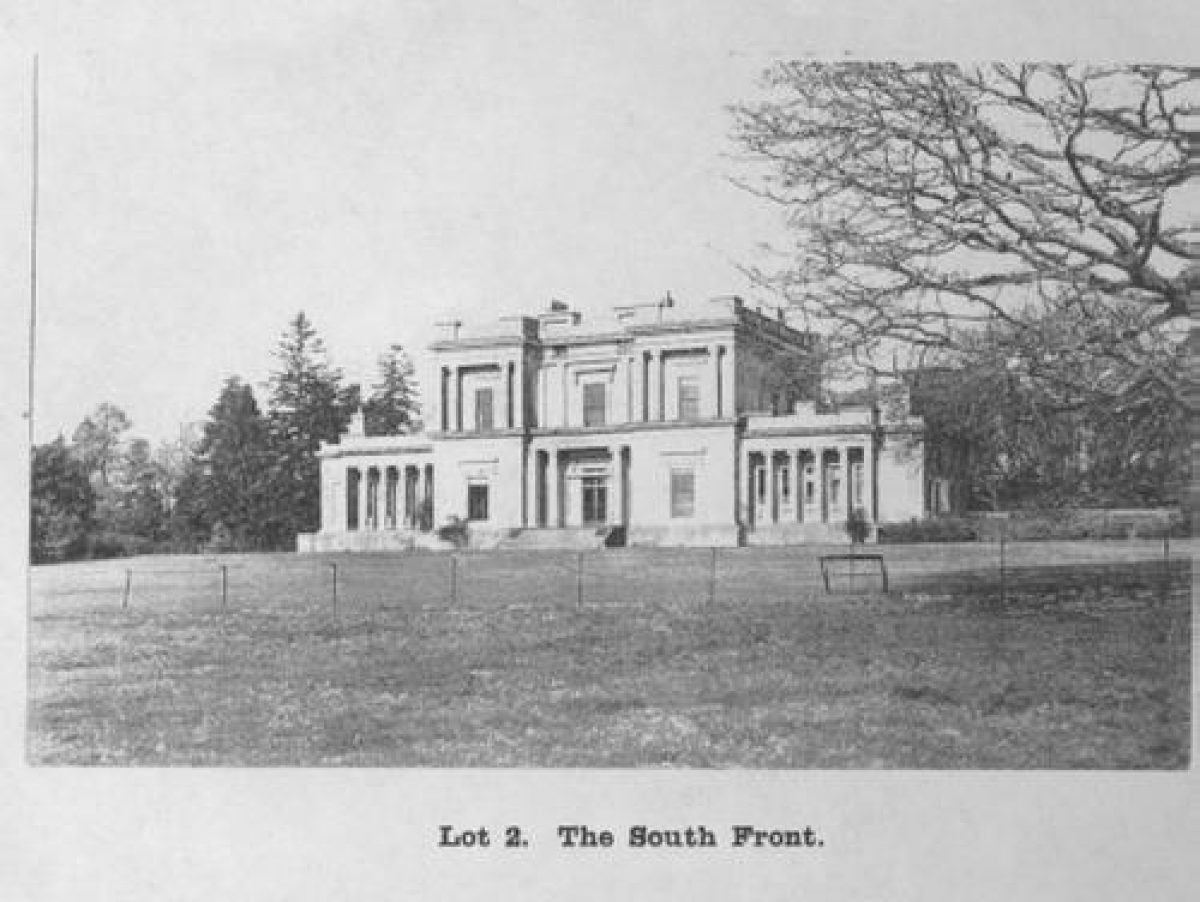

The estate of 1400 acres just north east of Rogate was previously bought by Captain James Lyon in 1837, the land being mostly wooded and in agricultural use. The early maps show Dangstein as Dene Stone (Gardner and Gream 1795) and subsequently as Dangstone (Draft Ordnance Survey map 1808), but by 1850 it was Dangstein. Mr Lyon was a retired East India Company officer, who had inherited a substantial fortune based on Jamaican plantations. His house was built to the plans of the architect James Knowles and although imposing and with 18 bedrooms, it was known to be draughty and hard to heat. The huge boilers consumed vast quantities of coal and the domed hall took three days to warm.

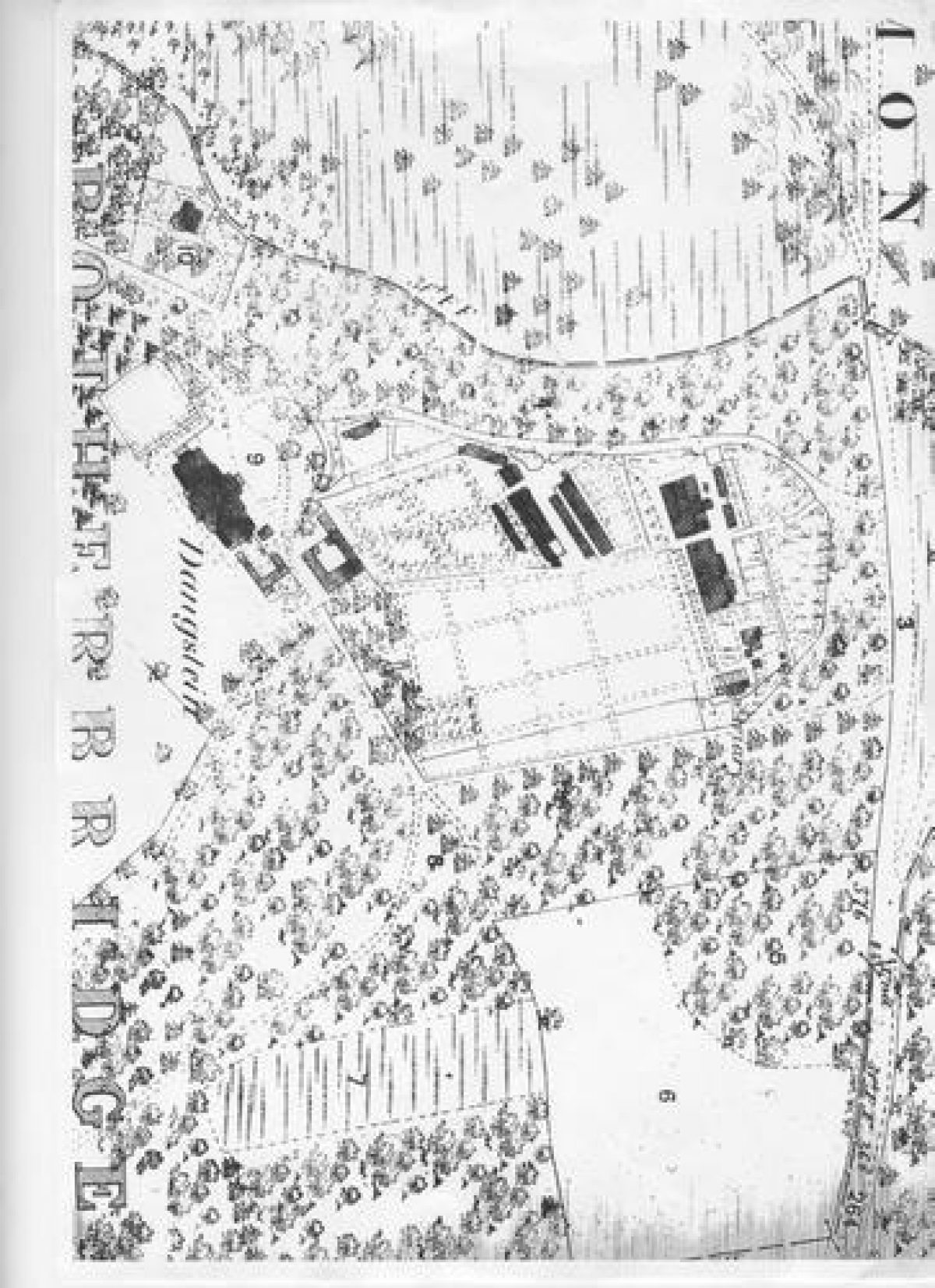

The gardens were not extensive, and the estate map of 1850 (West Sussex Record Office, Add. Ms 52421) shows to the south of the house a terrace, grass and a ha-ha or fence between the grounds and the parkland of 42 acres where the land is open to the magnificent views to the South Downs. To the north-east is the substantial stable block and behind is the walled kitchen garden together with a garden alongside the kitchen garden and an orchard. Woodland walks predominated.

Lady Dorothy therefore had a blank canvas to work on and this she instantly started to do. Within five years, the gardens of 23 acres were said to 'vie with most of our finest gardens in the richness of its collections of fine exotic plants'. Reginald expected his wife to run the house and gardens as his interests lay in farming, shooting and coaching. Her other preoccupation was to make Dangstein a destination for those eminent in politics, literature or science and the arrival of the railway at Petersfield, with a connection to Rogate, made this much more possible. Previously, journeys from London consisted of rail to Godalming and then by coach to an inn on the Portsmouth road.

In Exotic Groves, Guy Nevill writes that 34 gardeners worked day and night scooping out dells, ponds, sunken lawns and terraces, planting magnolias, weeping holly, Wellingtonias, bamboos, pergolas and herbaceous borders. Lady Dorothy imported tons of earth to level a small valley to the east of the walled garden for growing more vegetables and fruit. Terrace walks and winding broad gravelled paths took the visitor around the garden. To the west of the house was a parterre and an extensive pinetum. To the east a path known as Lady Dorothy's Walk led through a wood.

Lady Dorothy's great interest was exotic plants and she bought avidly. Sir William Hooker was an early visitor and plants were soon being exchanged with Kew. These exchanges and letters were continued by Sir William's son, Sir Joseph Hooker. Birds and animals also figured. The double aviary at Dangstein is still there, with a pheasantry in two compartments, two small pigeon lofts above and a small aviary for her exotic birds. Her whistling pigeons perhaps caused the most amazement.

In her Reminiscences, she wrote: 'I had sent to me from China a number of pigeon whistles made out of gourds, which were something like small organ pipes and could be attached with great ease to a pigeon's tail. The effect produced by the flight of these birds with whistles attached was extremely pretty, resembling Aeolian harps, the whistles being all of a different note. People used to be considerably astonished at such heavenly music, and their bewilderment and puzzled faces afforded me great amusement. No-one but myself, I believe, has ever organised such a winged orchestra...' So there was plenty to entice and entertain those important visitors that Lady Dorothy wished to see at Dangstein. She succeeded too, as amongst her visitors was Disraeli, who became a great friend.

Amongst the 34 gardeners working at Dangstein was James Vair (1825-87), her loyal head gardener who had previously been employed by Sir Walter Scott as a gardener at Abbotsford. He was particularly skilled in growing difficult plants, particularly orchids. Mr Vair was a meticulous man who kept the glasshouses in immaculate order, this being commented upon by those writing about the collections.

To house these collections, seventeen glasshouses were built both behind and alongside the kitchen garden, the walls of which were 'clothed in choice fruit trees', as was to be expected in a productive Victorian kitchen garden. The glasshouses consisted of a magnificent Palm House with a domed roof which measured 80 feet x 50 feet, a range of hot and orchid houses comprising three vineries and two orchid houses heated by hot water and a peach house. There was a range of houses containing an orangery, orchid house and succulent house, and a conservatory, fernery and small museum, together with associated forcing pits with 21 lights and potting sheds.

The collections were of orchids, ferns, insectivorous plants and aquatic plants. There was an extensive collection of trees from the tropics and sub-tropics, including fruit-bearing, economic and ornamental species. Bob Trotter writesthat at first, these were all housed in the palm house, then known as the tropical fruit house. Later, most of the fruit-bearing trees were moved to the tropical orchid house or orangery.

Reginald and Lady Dorothy lived on at Dangstein and their house in Charles Street in London until 1878 when Reginald died of cancer, having suffered for three years. He left Dorothy a life interest in Dangstein and an annuity of £2,000 a year, together with an annuity from her marriage settlement. She quickly realised that this was never going to be enough to run the estate and after some time of reflection, the Dangstein estate was put on the market and sold on 20 June 1879 for £53.000. The Rectory at Trotton was retained and was subsequently lived in by her son Edward and his wife Edith.

Lady Dorothy had hoped that her collections could have been bought from public funds and to have gone to Kew but this proved impossible. A sale of the plants by auction was arranged. The large tropical and sub-tropical trees were not included in the sale and were sold privately to the King of the Belgians, 'to fill his large conservatory', and to the Prince of Monaco. Lady Dorothy kept the orange trees for her conservatory at her new home.

That year, Lady Dorothy moved to Stillans, near Heathfield which she leased from her friend Robert Hogg, the pomologist, to a 'wilder, smaller, less formal garden needing far less upkeep'. James Vair accompanied her and bought three vanloads of plants from Dangstein. Around 1894 even Stillans was proving too much so she moved to Tudor Cottage at Hazlemere. From there she could drive to visit her son at Trotton Rectory and she would drive to Sutton Place to visit her friends, the Harmsworths. She continued to live in London but she could not quite give up her life in the country. She died in 1913 aged 85, having remained fit and well but a little vague until just before the end of her life.

Dangstein was bought by Charles Lane, a London solicitor, who dismantled many of the glasshouses and created an attractive parterre in the partly levelled valley. He died suddenly in 1912 but his widow and daughter stayed on until finances forced a sale in 1919. Developers bought the estate but found no buyers.

In 1926, when the house was again being advertised for sale, it was bought by Walter Quennell who began the restoration of the gardens. He demolished the house, which by this time was partly derelict, and built a more modest and comfortable house just south of the footprint of the 19th century mansion. Mr Quennell died in 1966 but his daughter, Miss Joan Quennell, at one time MP for Petersfield, still lives at Dangstein and continues the restoration and indeed to improve the gardens. New plantings of trees have replaced the devastation of the 1987 hurricane and the remaining glasshouses are in use as a commercial business.

Period

- Post Medieval (1540 to 1901)

- Victorian (1837-1901)

- Features & Designations

Designations

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

Features

- House (featured building)

- Description: Walter Quennell demolished the original house and built a smaller, more practical replacement.

- Earliest Date:

- Garden Wall

- Description: The walled garden remains in use.

- Glasshouse

- Description: The glasshouses are again in use.

- Walled Garden

- Terraced Walk

- Path

- Gardens

- Parterre

- Pinetum

- Woodland

- Key Information

Type

Garden

Purpose

Ornamental

Principal Building

Domestic / Residential

Period

Post Medieval (1540 to 1901)

Survival

Part: standing remains

Open to the public

Yes

Civil Parish

Rogate