Joy Uings examines the life of Edward Leeds, plantsman and daffodil hybridist.

Edward Leeds, was born at Buile Hill, Pendleton on 9 September, 1802. He was the eldest of four children born to Thomas and Ann, daughter of Joseph Rigby of Swinton Park, Manchester.

Thomas Leeds, originally from Norwich, was a cotton manufacturer until his bankruptcy in February 1829. Brockbank records that his mill was destroyed by fire. He and Edward then set up together as Sharebrokers, a business Edward continued after his father's death in November 1839.

Edward married Ann Segar, of Liverpool, and the first of their four sons, also named Edward, was born in 1837, followed by Thomas in 1839. Each of these sons, and possibly also the youngest, Henry (born 1846), was to go on to qualify as a Doctor. Edward and Ann's third-born son, Francis Henry, died at just four months old on 28 September 1845.

Edward Leeds died at his home in Longford Bridge, Stretford, on 4 April, 1877 and was buried, five days later, with his infant son in Bowdon. Leeds' wife survived him by less than five years.

At one place the Veronicas had prevailed, at another the Saxifrages had gained the ascendancy. There were large clumps of the most beautiful Orobus vernus I had ever seen. Hardy Geraniums had grown into huge masses, and Fumaries formed lovely purple bosses.

Seedling narcissi: from Gardeners’ Magazine of Botany, 1851, p.169 The first three of Leeds’ seedling narcissi to be featured. Narcissi Leedsii is on the left.

Of the smaller Irises, there were large clumps. Creeping plants had trailed over the walks, and in the borders were thickets of huge growers, Telekias, Asters, Campanulas, Delphiniums, Veratrums, Heracleums, and other giants, in rank profusion, the fittest only having survived. On closer inspection the rockeries were found to contain choice treasures, hidden away amongst the overgrowth, and these were carefully marked down when in bloom, and removed when the proper time came.' 1

Passionate about plants

According to William Brockbank, Edward was educated at John Hathersall's school on Ardwick Green, Manchester, and even as a schoolboy was passionate about plants, spending his pocket-money on their acquisition.

He went botanising in Teesdale while on fishing trips with his friend, Thomas Glover, collecting plants for his herbarium and garden. He received plants and seeds from America, Europe and even the Crimea (via his brother-in-law). He was a correspondent of Canon Ellacombe of Bitton, and was well known to the leading horticulturists of the day. His garden was the meeting place for Lancashire florists. He was short-listed for the post of first curator of the Manchester Botanic Gardens, although this last ‘fact' has been shown to be almost certainly untrue.

Leeds' garden was at Longford Bridge in Stretford, about four miles from the centre of Manchester. The garden was about 1.25 acres in size, the perimeter planted with rhododendrons, box and laurels. Several years after his death, it still retained signs of its splendour among the general decay.'There were huge Paeonies, many lovely varieties of Scillas nutans and S. campanulata, of every shade of blue, lilac, pink, and white, the results of Mr. Leeds' careful crossing. In the rear of the cottage were some greenhouses and brickwork pits filled with small pots of Alpines, which had overgrown the place, making mats of Sedums and Saxifrages. In the greenhouse was a large lot of seedling Amaryllis, which had been carefully crossed. The rockeries were built up of brick, tier upon tier. There were four of them, each 100 foot long, about 10 feet broad, and 4 feet high, the spaces between the bricks were filled with Alpines and hardy plants, and now covered with rank overgrowth.

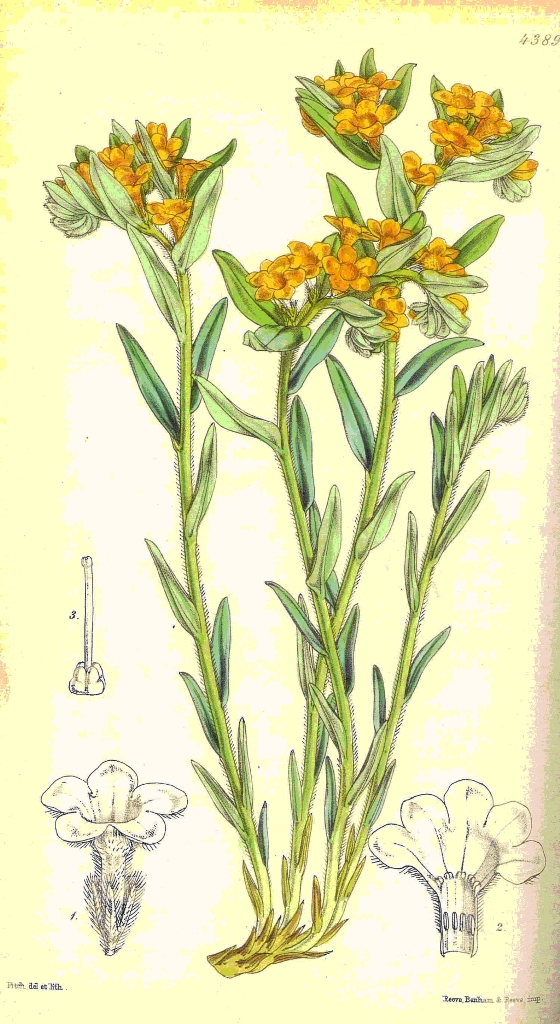

Lithospermum canescens: from Curtis’ Botanical Magazine, 1848, t.4389

Horticultural skill

Leeds' skill with plants can be found in the contributions he made to a number of gardening magazines.

Volume 4 of The British Flower Garden contained a drawing of 'three very distinct varieties' of Primula farinosa of which he wrote: 'The white-flowered variety is a very local plant, and rare in its native habitats. I collected it in very damp situations and loamy soil... The high-coloured variety is mostly found in bog or peat earth ... the specimens sent are not near so strong as I have grown them, by planting them in bog and loam, and placing the pots in which they were grown in pans of water in Summer...'

The Floricultural Cabinet of 1 December 1833, contains an article by Leeds 'On the Cultivation of Cypripediums'. Leeds had a considerable collection of the hardier forms - C. calceolus; C. pubescens; C. parviflorum; C. spectabile; C. humile and C. arietinum - and they required different treatment. He described the compost mixtures he used for each and noted that he 'planted grass round the edges of the pans ... because I find the roots of Cypripediums delight in running amongst the roots of grass'. He concluded his article: 'I had this season one root of C. pubescens, which produced fifteen flowering stems, and another root of C. Calceolus, with thirteen blossoms, - both of which have been grown from very small plants. I have also been most successful with C. spectabile.'

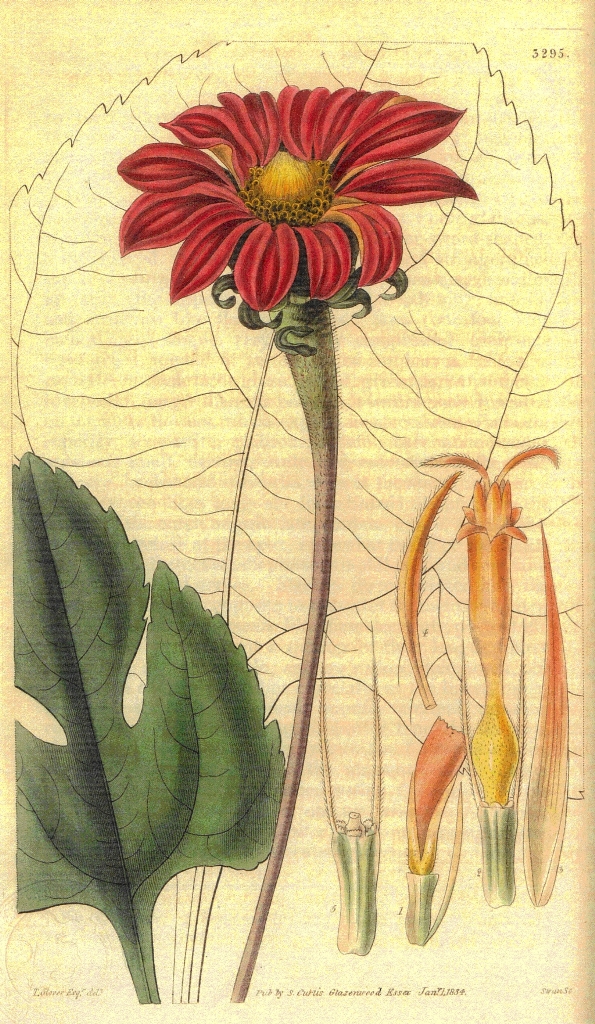

In the same year, Leeds raised Helianthus speciosus(the Mexican Sunflower, also known as Tithonia rotundifolia) from a packet of seeds from the Botanic Garden, Mexico, sent to him by his friend William Higson.

Helianthus speciosus: from Curtis' Botanical Magazine, 1834, t.3295

Thomas Glover made a botanical drawing of the plant which he sent on to William Hooker and which was published in Curtis' Botanical Magazine in November 1834. In his covering letter, Glover referred to Leeds as having 'lately commenced business as a florist, etc' and this became in print, 'Nurseryman and Florist'. There is no real evidence that Leeds ever made his living from his plants, although in September 1832, the Manchester Guardian carried an advertisement for Dahlias which stated: 'The admirers of these flowers are respectfully informed that a select and splendid collection of them is now in bloom in the garden of Mr Edward Leeds, Longford Bridge, near Stretford, and parties desirous of ordering for the ensuing season have now the opportunity of making their own selection. Also a very choice collection of ornamental Herbaceous Plants on moderate terms. Orders may be left with Mr G Vaughn & Son, seedsman, 13 Market Place.' It is unclear whether Vaughn & Son were selling Leeds' plants or whether Leeds was providing Vaughn & Son with a showcase.

Other plants raised by Edward Leeds that were featured in Curtis' Botanical Magazine were Tagetes corymbosa (1840); Stevia trachelioides (1841); Lithospermum canescens (1848); and Echinacea angustifolia (1861).

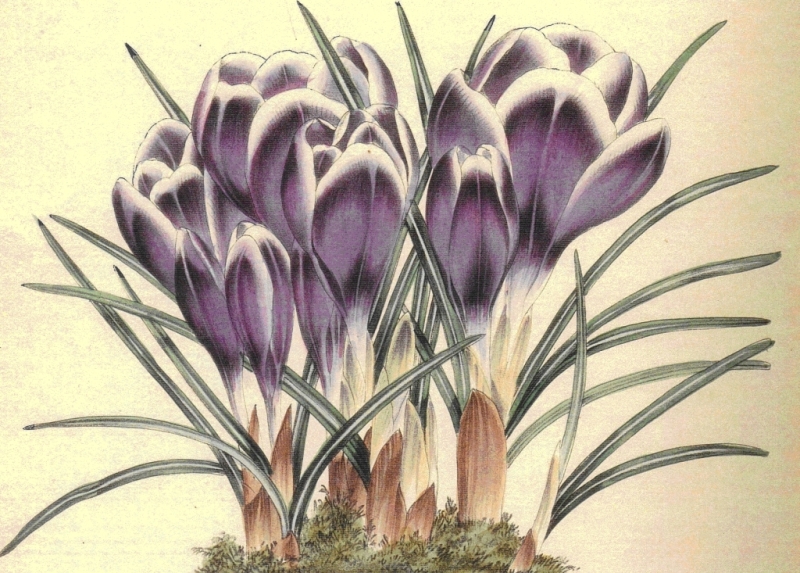

In 1851, the Gardeners' Magazine of Botany featured two plates of Leeds' seedling narcissi and also Crocus vernus var. Leedsii. This was the best of the many thousands of crocuses that he had raised and was described as 'a very striking improvement on any varieties we possess. The colouring is rich and dense, a deep violet-purple, which is set off in admirable contrast by a distinct pure white margin'. Although much admired, and despite Leeds holding a large stock, it does not appear that it was ever made available commercially.

Edward Leeds grew a huge variety of herbaceous plants. Reports of Manchester flower shows between 1829 and 1838 record that he won prizes for, amongst others, Trillium grandiflorum; Anemone thalictroides var. pleno; Streptopus roscus; a Campanula of unknown variety; Diphylla cymosa; Viola lanceolata; Lilium superbum var; Dracocephalum argunense;Cypripedium Pubescens. In 1838 he won the premier prize for Peonies.

One of Leeds' favourite plants was Echinacea angustifolia. In 1870 he wrote that he had 'never yet parted with any'. He had provided a specimen for Hooker, and it had been featured in Curtis' Botanical Magazine on 1 November, 1861. Leeds had shared his seeds around, and the plant had been grown by Mr Ross, of Smedley.

Receiving and sharing

Edward Leeds received seeds and plants from many different sources and was always on the look-out for plants new to cultivation in Britain. Giles Duxberry sent seeds from Missouri and Leeds' friend, William Higson, sent him seeds from Mexico. Higson was not himself a gardener or botanist and only obtained the seeds to oblige Leeds. Yet Leeds always sought to give Higson, rather than himself, the credit for any new introduction.

In 1870 Leeds wrote about some new plants that he had raised, from seeds sent by Mr. Bourne of Iowa. It provides us with an insight into his passion and his methods. 'The seeds were collected by a gentleman who knows nothing about plants: at my suggestion during his rambles he picked pods of anything he met with wild and put all mixed together in a Bag and sent them to me.

Crocus vernus var. Leedsii: from Gardeners’ Magazine of Botany, 1851, p.305However

He appears to have stumbled upon some fine things. I raised many others mostly now lost. It is clear I think that much may be done by parties not acquainted with plants if requested to get wild seeds promiscuously and not ask for names to, which deters such parties from trying.' This approach meant that he was often seeking identification of the resultant plants.he also received seeds and plants from more knowledgeable sources. John Goldie, the Scottish botanist, sent him plants from Canada, including a white dwarf Asclepias, the Orchis dilatata (Habenaria dilatata), an unidentified Phlox, Golden Rods, and Asters.

A few of Leeds' letters survive in the archives at Kew: eight to Sir William Hooker; seven to Sir Joseph Hooker and one to William Thiselton-Dyer, plus three to Thomas Glover which were passed on to Hooker.

As a correspondent, Edward Leeds says nothing about himself or his family (unlike Thomas Glover who counted himself a friend of both William and Joseph Hooker). His letters are all about plants, often seeking identification, hoping that he had grown something new and unknown. They are always short on detail. He had 'an Alstroemeria from Bolivian seed', lupins from Texas and California, and melon seeds 'from the borders of the Sahara', brought to Manchester by a 'Turkish gentleman'.

The plant-hunter Thomas Nuttall botanised throughout America, but returned to Lancashire when he inherited his uncle's estate. He visited Leeds and admired some asters which had come from Missouri, saying 'they were new to him'. Leeds promised to send them to Kew in the autumn, once they had finished flowering and reported that he had visited Mr. Nuttall's house, but found him 'in very poor health'.

It was Leeds' friend Thomas Glover who introduced him to William Hooker and Glover acted as a go-between for several years. In November 1842, the year after Hooker became Director of Kew Gardens, Glover wrote: 'Through the kindness of my friend Mr Edward Leeds I have been enabled to send you a few out of the list of plants you furnished me with as desiderata in your British Garden. Some I know I have sent you before but he has added them unasked for. He has also added a few other things not British which he would be delighted to hear were any of them new to your collection...'

Glover knew that Edward Leeds was prepared to share his plants, and in return, wanted to do something for him. He gave Hooker a list of the plants Leeds particularly wanted at that time: 'allium caeruleum, Primula denticulata, Aquilegia skinneri and Polemonium caeruleum var. grandiflorum... Also any description of Ixia and its kindred tribes'. It was the beginning of thirty years of plant-exchanges between Manchester and Kew. In 1870, Leeds reported that the pisum umbellatum he had received from Kew was flowering well, and in 1871 he sent to Kew a basket of plants, including several Sempervivums, Silene catholica, Polemonium grandiflorum, Potentilla pulchra, Chrysanthemum arcticum and an Inula.

Less than a year before his death, and in failing health, he offered his herbarium to Kew. It was accepted and a letter of thanks was sent to him on May 23, 1876.

Daffodil hybrids

Although Edward Leeds grew a wide range of plants, and was known locally for his florists' flowers, it is for his daffodils that he is remembered.

It is not known when he began his hybridising experiments with daffodils, but six of his seedlings were featured in The Gardeners' Magazine of Botany in 1851. He went on to produce thousands of bulbs of 169 different varieties, which he tried to sell for £100.2 Peter Barr heard of them, but could not afford the price (around £7,000 - or £59,000 using average earnings - at today's values). The story, likely to be apocryphal, is that Leeds made a will stating that if the bulbs had not been sold at his death, they and all his papers were to be burnt3. In the event, Barr was able to raise £75 in a cartel with various other enthusiasts.

They purchased '24,223 bulbs, besides a lot of small ones, not yet flowered'. Half went to Peter Barr, 30% were split equally between Rev John G. Nelson, Mr W. Burnley Hume, Mr Herbert J. Adams and G. J. Brackenbridge, and the remaining 20% went to a Dutch nurseryman, Mr Peter Van Velsen of Overveen.4Barr also purchased the bulbs raised by William Backhouse. Neither Backhouse nor Leeds had left details of what species or varieties had been used as parents and much time was spent sorting and classifying the bulbs.

Seedling narcissi: from Gardeners’ Magazine of Botany, 1851, p.289

Earlier attempts at classification were no longer considered entirely useful. The new additional classifications - Barrii, Leedsii, Humei, Backhousei, Nelsonii and Burbidgei - celebrated those men who had been instrumental in raising the new hybrids. The names described particular types, and all types had some from each hybridist. It has sometimes been mistakenly assumed that Edward Leeds raised all those classified as Leedsii. In fact, Leeds-raised hybrids were to be found in all of these groups (except Backhousei, which in 1884 only contained four varieties) as well as in groups with the older names such as major, incomparabilis, bi-color and so-on. Indeed there were slightly more Backhouse varieties than Leeds varieties in the Leedsii division. To make matters more confusing, Narcissus Leedsii (as figured in 1851) was in the Incomparabilis group.

Edward Leeds' name was given to the division of narcissus described as '(Montanus x Pseudo-Narcissus, or perhaps Albicans x Poeticus), flowers horizontal or drooping with a long slender tube, spreading and sometimes dog-eared, pallid perianth, and pale cup, varying from canary yellow to whitish, generally dying off white; and it is in the paler hue of its cup the varieties of Leedsii differ from the white varieties of Incomparabilis.' 5

The suggested classification was accepted at the RHS Daffodil Conference held on 1 April 1884. After a long period during which it had been an unfashionable plant, this was the first step in daffodils becoming today's ubiquitous spring flower. Hybridisation continued and in 1950 it was necessary for a new classification system to be adopted. Edward Leeds' name disappeared from plant taxonomy.

Very little was known about Edward Leeds. William Brockbank lived in Didsbury, only a few miles from Leeds' home in Stretford, but had never heard of him. He was at the daffodil conference and went home determined to find out more. In his 1894 article he wrote that he visited Leeds' garden in the Spring when 'the garden was ablaze with Daffodils - growing by thousands, almost wild'. But there were also many choice plants which Brockbank removed to his own garden 'where they now abound and constantly remind me of Leeds of Longford'.

What sort of a man?

What sort of a man was Edward Leeds? Certainly a skilled gardener; undoubtedly an enthusiastic seeker after new plants. But descriptions of him are rare.

Thomas Glover described him in one letter to William Hooker as someone who 'would give you a share of anything he had whatever it had cost him' and in another he wrote 'I never met with an individual so feelingly alive to any little favour conferred, or more anxious to make a return'.

Mr. Findlay, the curator of the Manchester Botanic Gardens at the time Brockbank was researching his article, described Edward Leeds as ‘an enthusiastic botanist'. Brockbank wrote: 'Mr Findlay says that Leeds had a deep, glowing childlike enthusiasm for nature as set forth in the vegetable world. He always thought him destitute of malice or guile; firm in his attachments; in short, the "fine fat fellow that he was".'

In 1914, in Luther Burbank's His Methods and Discoveries, Their Practical Application, Vol.1, the following description is given of one of the early daffodil hybridists. Although it doesn't say that it is Edward Leeds, the description fits all that we know of him: '...[he] was a highly sensitive, nervous, shrinking man, with a great eye for detail, a true appreciation of values, a man who looked beneath the surface of things and saw beauty in hidden truths, a man who thought much and said little.'

Echinacea angustifolia: from Curtis’ Botanical Magazine, 1861, t. 5281

Edward Leeds was a quiet, unassuming, self-deprecating man, with the heart of an explorer, but without the personality to match his inner ambitions. Plant-hunting was generally for the energetic and fearless; the risks were enormous and many lost their lives while seeking out new plant introductions. Edward Leeds had a different approach, less physically demanding, but requiring considerable ingenuity. Instead of going out to find the plants, he had friends and contacts who could provide him with seeds of unknown origin. He would then use all his skill to nurture those seeds to give life to what he always hoped would be a ‘new' plant. Yet, when he was successful, his modesty led him to give credit for the introduction to others.

Sources

Uings, Joy. Edward Leeds: a Nineteenth Century Plantsman. A dissertation submitted to the University of Manchester for the Certificate of Continuing Education in Garden and Landscape History, 2003.

Brockbank William. The Gardeners' Chronicle, November 10, 1894 p.561-2 and November 24, 1894, p. 625-6

Kew Archives. Letters from Edward Leeds and Thomas Glover to Sir William Hooker and Sir Joseph Hooker.

Endnotes

1. William Brockbank was the author or a two-part article about Edward Leeds which appeared in the Gardeners' Chronicle in 1894. He made the assumption that Rev Herbert, who became Dean of Manchester in 1840, was the motivating force. Herbert had published, in 1836, his work on Amaryllidaceae where he had stated his suspicion that many so-called narcissus species were in fact hybrids. He went on to produce a number himself.

2. In 1903, Barr & Son had only a few bulbs of a new daffodil for sale. Each bulb was priced at 50 guineas.

3. Leeds' Will, as terse as his letters to Hooker, was drawn up on 4 November 1868 and left everything to his wife.

4. Not all reports include mention of Mr. Van Velsen.

5. Ye Narcissus or Daffodyl Flowere, Barr & Son, London 1884 p.39