Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild was, in the words of the Princess Royal to her mother, Queen Victoria, ‘an excellent gardener and a good botanist'.

Sophie Piebanga looks at his work and the legacy that lives on today in the garden he created at Waddesdon in Buckinghamshire.

Early influences

Born in Paris on 17 December 1839 into the well-known family of bankers, Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild's interest in gardening was stimulated from an early age. His mother Charlotte (1807-1859) was a keen gardener and gave each of her children a plot of ground at the family farm of Neuhof, just outside Frankfurt, where she had set up a dairy, complete with a Derbyshire dairy maid.

‘To these [plots] we attended with much zeal and gravity, though were it not for the assistance of the gardener it may be questioned whether they would have produced anything but weeds,' Ferdinand later wrote [1].

Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild

Providing small garden plots for one's children to encourage healthy physical activity and to educate them in the natural world, appears to have been part of Victorian life. At Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, Prince Albert Edward, Ferdinand's future close friend, was also made to garden by his parents, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Gunnersbury

Ferdinand's mother was also a Rothschild, the daughter of Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836), whose family home was Gunnersbury in England. Early visits to his mother's childhood home also left their impact on the young Ferdinand. In his ‘Reminiscences' (1897) Ferdinand recalled how, as a child, he was much impressed by the vast number of market gardens near London.

He also remembered once being taken to see the ‘famous glasshouses of Mrs Lawrence, the mother of Sir Trevor' [the then president of the Royal Horticultural Society], and he continued, ‘they much impressed me for at Frankfurt ‘glass' was then unknown' [2].

The gardens and glasshouses at Gunnersbury likewise were highly valued by Ferdinand - as was their produce! ‘How greatly I appreciated the contents of the Gunnersbury "glass" can hardly be understood now, when South African, Australian and American peaches, and Brazilian pines [pineapples] are as common as gooseberries,' he wrote [3].

Other early horticultural experiences included, in 1851, a visit to the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, which had as its centrepiece Joseph Paxton's huge glasshouse, the Crystal Palace. Ferdinand later recalled especially the two stately elms that had to be accommodated inside the glasshouse complex.

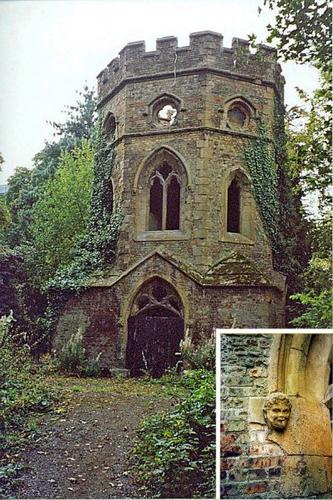

Pulhamite boathouse, Gunnersbury

Gruneburg

In 1845, when Ferdinand was about six years old, the first stone was laid for Grüneburg. This was to be the family's summer house, outside Frankfurt. Ferdinand recounted how his mother enjoyed laying out the grounds. Twenty acres were made into flower gardens and orchards, complete with aviary and pond, the latter stocked with fish and ‘ornamented' with ducks [4].

Charlotte also planted an avenue of chestnut trees. ‘There was a mound which we called ‘the mountain' in a remote corner containing the ice-house, and close by were enclosures for a wild antelope and a tame deer that my Father had brought from Egypt,' Baron Ferdinand recalled [5]. Garden features such as these were later to be found at Waddesdon Manor, for example an aviary, a duckpond and enclosures for animals.

At Grüneburg it was not just the garden but the model farm too that held attractions for Ferdinand. Many a happy hour was spent playing in the farmyard, which no doubt fired his enthusiasm for animals like cattle [6].

Schillersdorf

Another property that held many happy memories for Ferdinand was Schillersdorf at Moravie, near D'Opava in Silesia. Baron Ferdinand's grandfather Salomon de Rothschild (1803-1874) bought the property in 1842, which his father Anselm inherited in 1855. Anselm made many alterations to the site, turning it into a model agricultural estate [7].

Every autumn Ferdinand would spend up to three months at Schillersdorf, hunting and shooting. ‘The house...was in the centre of a small park, which was at once much enlarged by my father, and my mother assisted in laying it out and planting it,' he wrote [8].

Schillersdorf was the place where Ferdinand took his new bride and cousin Evelina (1839-1866) for a long honeymoon after their wedding in the summer of 1865. Contemporary letters from Evelina to her parents Lionel (1808-1879) and Charlotte (1819-1884) back in England reveal the extensive operations going on at that time, instigated by Ferdinand's father Anselm.

Large trees were being transplanted and a huge lake created by means of gunpowder and much manual labour. Evelina described how her father-in-law ‘has ... surrounded his cottage with rocks, cataracts and bridges but they are all too juvenile to be romantic' [9].

She continued: ‘like other Rothschilds, his greatest hobby is a fountain, 80 feet high, which was arranged in one of the lakes when the pipes were laid down for watering the grass'. A pretty redbrick castle, near the river Oder, contained the machinery for the water works.

Evelina also described how wild vine, planted by Anselm to climb through the large oaks and elm, was colouring the park bright red that autumn. Accounts of the gardeners struggling to contain the wildlife that was digging up the lawn, have a familiar ring to them!

At Schillersdorf the work was carried out under the guiding eye of a Mr Exner, who was described by Evelina as ‘a second Joseph Paxton'. Mr Exner was also entrusted with organizing the ‘Volksfest', a party for all the estate people. This event can be compared with Ferdinand's later ‘Baron's Treat', the annual festivity when everyone from Waddesdon and the surrounding villages were invited to a picnic and fair held in the Manor grounds.

Waddesdon Manor

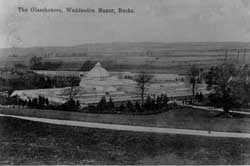

These early horticultural influences and impressions came to fruition when Baron Ferdinand bought his own estate near Aylesbury, in the autumn of 1874 from the Duke of Marlborough.

No sooner had he bought it than he began to plan a grand country house on what was essentially a bare hill, known as Lodge Hill. A letter dated February 1875 [10] describes how Ferdinand was pleased with the progress made in the plantations. Early photographs indeed show young trees already in place whilst the carriage drive was still being laid out and the foundations for the house were barely dug.

In the initial layout of the grounds, Ferdinand was aided by the French landscape gardener Elie Lainé, who was ‘bidden to make designs for the terraces, the principle roads and plantations'.

In his ‘Red Book' Ferdinand made it clear, that although Lainé was involved with ‘the chief outlines of the park', he himself was responsible for much of the ornamental plantings: ‘the pleasure grounds and gardens were laid out by my bailiff [George Sims] and gardener [Arthur Bradshaw] according to my notions and under my superintendence' [11].

As his father had done at Schillersdorf, and as his relative and friend Lord Rosebery (married to Ferdinand's cousin, Hannah) did at Mentmore, Ferdinand transplanted large trees, using Percheron mares.

Construction at Waddesdon, 1870s

The south terrace, 1897

‘My trees came - some of the - from Wooburn [sic] Abbey...and some from Claydon House - Sir Harry Verney's place. Some from Halton; some from Drayton Beauchamp - wherever I could get them. Yes, they turned out as we wished...with the exception of the oak. The oaks have given trouble; but the chestnuts have done remarkably well' [12].

In some of his obituaries, it is suggested that when it came to the planting of trees, Ferdinand lost patience at times, wanting instant effect when he could not have it.

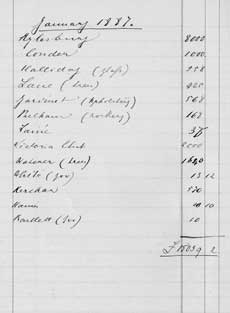

Apart from tree planting, there were extensive tracts of shrub planting. The account books show particularly large orders from the nurseries of Anthony Waterer and H. Lane & Sons, suggesting that they supplied most of the trees and shrubs.

Much planting was carried out in accordance with the colour theories of the nurseryman William Paul [13]. Contemporary reports in the horticultural press describe large plantings of single varieties of different colours adjoining one another.

One source describes the ‘plantations of spruce and firs, of golden yews and elders, of variegated maples and laurels...disposed between the hilltop and the village' [14].

The order book of Waterer's nursery of 1897/8 shows large numbers of genista, spirea, yew, box, dogwood, privet, buckthorn and quickthorn ordered for Waddesdon, as well as 500 ‘heath of sorts' and small numbers of individual trees such as acers, lime and cupressus.Reports of Ferdinand's annual ‘Treat', which appeared in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News from 1880 onwards, provide a glimpse of the development of the grounds at Waddesdon. The July 1881 account, which still refers to the property as Lodge Hill, reads:

'The slope on the south side of the mansion is formed into terraces, and several fine statues lend embellishment to the scene. Though the exterior of the fabric has now been completed, only a portion is at present rendered habitable, and it was in this part that the Baron had entertained the Prince of Wales and a select company the previous day. Even the windows have not yet been added to the great majority of the apartments, but temporary boarding cover the apertures. The grounds in the vicinity are laid out in pleasant walks and shrubberies; on the east is a well-formed lawn, on which the Prince and the Baron's other guests spent the Sunday afternoon, and a little to the east is a large ice-house, the approach to which, arched over with huge and rough blocks of stone, presents a somewhat romantic air. Wandering northward from here the visitor reaches a spot whence the view is no less expansive and grand then that seen from the south' [15].

Pulham rockwork

Extensive rockworks were constructed throughout the gardens by the firm ofJames Pulham & Son. Their work at Waddesdon was extensive, being on an even larger scale than their hitherto best-known rock work for the Prince of Wales at Sandringham.

One of the Pulham hallmarks was the so-called Pulhamite, an artificial composite, made to resemble real rock. However, at Waddesdon mostly real rock was used, including limestone. Natural rock would have been easy to come by, since large quantities of it were excavated during the levelling of the hilltop in preparation for the building of the house.

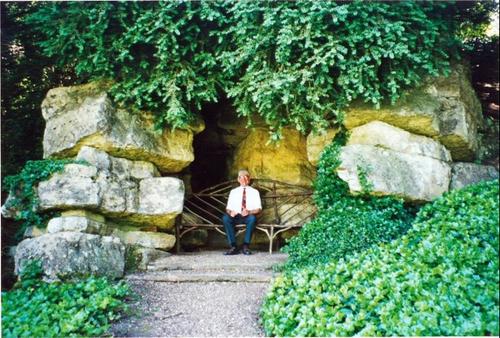

Pulhamite grotto at Waddesdon Manor

In his ‘Red Book' Ferdinand refers to the ‘deep gash' in the side of Lodge Hill when he first bought the property in 1874. This gash, he remarked, the result of limestone quarrying, proved ‘most useful in the construction of rockeries, and has since been converted into a basin and fountain' [16].

There was further rockwork in the Aviary and in the garden near the Dairy (laid out by 1885) with adjoining lakes created for ornamental wildfowl [17]. Again, these features are an echo of the dairy and lakes at Neuhof.

By 1887 the garden was virtually complete. In August of that year, the Bucks Advertiserreported on the annual ‘Baron's Treat':

'The best attraction ... in the estimated opinion of many present, was the ornamental portion of the Park, which was as usual thrown open. The fountains were in play, and, together with the beautiful parterres of flowers around them, were gazed at by continuous streams of visitors; the aviary too attracted notice; and walks among the shrubberies, which, with advancing age, are steadily progressing in picturesque beauty, were also enjoyed' [18].

The same year saw a new head gardener, John Jaques, replacing Arthur Bradshaw. Although most of the features of the garden were already in place by then, Jaques would have been involved with laying out the rose garden, one of the last additions to the garden before Ferdinand's death in 1898.

Practical gardening knowledge

According to Marcel Gaucher, gardener to the Rothschild family for many years, Ferdinand, though interested in gardening, left the actual work to his estate staff. This was in contrast to his sister Alice who concerned herself deeply (perhaps to the point of interfering?) with her gardeners and their work.

Ferdinand did, however, have considerable knowledge about the cultivation of plants. On a trip to Algiers in 1886 he bought a large number of palms (no doubt destined for the glasshouses at Waddesdon). Reporting back to Lord Rosebery, Ferdinand wrote: ‘If she [Hannah] does buy trees mind that they have been for some time in pots or tubs and are not taken out of the ground to be exported' [19].

Aerial view of Waddesdon

This image of Ferdinand as a practical gardener is confirmed by an article in 1898 in the Gardener's Chronicle which states that ‘not only did [Baron Ferdinand] like plants but ...[he] had acquired a considerable knowledge of them - a trait which is characteristic of all the Rothschilds' [20].

Most telling is the diary entry of the Earl of Crawford, David Lindsay, who stayed at Waddesdon in June 1898. He wrote:

'... it is in the gardens and shrubberies that he [Baron Ferdinand] is happy. He is responsible for the design of the flower beds; for the arrangement of colour, for the transplanting of trees; all these things are under his personal control and I was astonished at the knowledge he displayed: I don't mean about botanical lore but about the history of the place. Every tree and shrub has been placed and planted by him for the place was bare upland when he bought it twenty years ago. Point to an oak or a maple and he will tell you precisely when it was planted, whence it was transplanted or wither it shall be moved in the autumn.'

And Lindsay added: ‘It is only when among his shrubs and orchids that the nervous hands of Baron Ferdinand are at rest' [21].

Orchid grower

No mansion was complete without an extensive range of glasshouses and Waddesdon was no exception. Situated between the stables and the dairy, on the lower slope to the north east of the manor, the glasshouse complex, known as ‘Top Glass', adjoined a layout of formal flowerbeds, called ‘Paradise Garden', and included a large palm house.

Some of the glasshouses were given over to specific groups of plants such as anthurium, orchids and Malmaison carnations. The latter were also known as ‘Rothschild carnations', on account of their popularity with members of the Rothschild family, who grew them on a grand scale [22].

Display glasshouses at Waddesdon in about 1890

Other glasshouses were devoted solely to orchids. Like so many of his relatives, and as was fashionable at the time, Ferdinand had a strong interest in this species. In a letter to his aunt Charlotte he explained how his liking for them was based on their intricacies as much as their beauty [23].

The five glasshouses at Waddesdon Manor, filled in 1885 with choice species and varieties of orchids, were said to be only the beginning of Ferdinand's hobby [24].

The orchids came from a variety of sources such as William Bull, William Marshall, Protheroe and Shuttleworth, B.S. Williams and Stuart Low. The majority, though, appear to have been supplied by the so called ‘orchid king' of the time, Frederick Sander.

It was Sander who named a variety of orchid after Ferdinand, namely Odontoglossum wilckeanum var. Rothschildianum. Sander first exhibited the orchid at the Royal Horticultural Society's Great Flower Show, in May 1890. ‘The great beauty of the plant caused quite a sensation, and attracted the attention of his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales and other distinguished amateurs present', Sander wrote [25].

Baron Ferdinand also had a wild species orchid (as opposed to a variety) named after him in 1888, Cypripedium rothschildianum 'Reichenbach' (1888). This was re-named Paphiopedilum rothschildianum (Stein) in 1892. It is found in the wild on Mount Kinabalu in Borneo and is today extensively used for the production of hybrids [26].

Contribution to Sandringham

It is interesting to note that Ferdinand apparently influenced the layout of a garden other than Waddesdon. In fact it was no less a property than royal Sandringham which became the subject of his views and ideas.

Sandringham was the Norfolk retreat of Albert Edward (‘Bertie'), the Prince of Wales and his Danish wife Alexandra. Acquired by Queen Victoria in 1862 for her somewhat wayward son, the house was rebuilt between 1867 and 1870.

Ferdinand had long been part of the circle of friends surrounding the Prince of Wales, who himself became a regular visitor to Waddesdon Manor. No doubt Ferdinand also stayed at Sandringham.

The lake and Pulhamite boat cave at Sandringham

He would have been familiar with the gardens that were laid out surrounding the new house in the early 1870s by William Broderick Thomas, with much rockwork by James Pulham.

Correspondence from the early 1890s from the Prince of Wales to Ferdinand indicates that, besides finding him a gardener, Ferdinand also provided his friend with advice on alterations to the garden, which the Prince of Wales came to refer to as the ‘Rothschild Sandringham improvements' [27].

In July 1891 he wrote to Ferdinand:

'I am most grateful to you for all the trouble you have taken in arranging the new flower garden at Sandringham. I shall be very curious and interested in receiving the new plan from Probyn & I have but little doubt that it will meet with my approval especially as it will enlarge the flower garden, straighten the walks and alter the view to the Church wh. is most desirable' [28].

Sir Dighton Probyn was the comptroller at Sandringham. Privately he expressed concern about the expense of the improvements, but the Prince of Wales was keen to press ahead: ‘I have sufficient confidence in your good taste to be quite easy in my mind that it will be a success', he wrote to Ferdinand [29].

The correspondence also relates to the erection of a circular fountain. Writing in the late summer of 1891, the Prince of Wales agreed with Ferdinand's suggestion to prepare the ground for the fountain, so as to show its location, but to defer the placing of it until the following spring. This would allow sufficient time for the basin to be made. During the intervening months, Ferdinand suggested, the area could be planted with shrubs and winter flowers. The latter might well have included pansies, Princess Alexandra's favourite flowers.

It is difficult to ascertain to what extent Ferdinand's proposals were actually carried out. Apart from a small number of later letters, few others survive that might have revealed more information. Also, a fire at Sandringham in 1891 might conceivably have deferred any garden improvements, especially as these were considered rather expensive by the comptroller Probyn in the first place. In addition, in early 1892, the Prince and Princess lost their son, Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence. No doubt this sad event would have taken their minds off any garden works.

Ferdinand also presented the Prince of Wales with a ‘bronze group' for the garden at Sandringham, which the latter (writing in a letter thought to date from 1891) considered as 'a lasting memento of the valuable advice you have given me on landscape gardening' [30].

It is not clear whether this ‘bronze group' is in fact the same fountain given by Baron Ferdinand to the Prince of Wales, which the then Duchess of York (the future Queen Mary) described, in 1898, as ‘hideous...it consists of a large bronze pelican sitting on a rock, & it spits out water from its huge beak, when Mackellar turned on the water I roared with laughter at this truly ludicrous sight. It really is too awful!' [31]

Today the pelican fountain survives, albeit in storage. Damaged during the war, when it served as a shooting target for bored soldiers, it is currently undergoing restoration.

In the autumn of 1898 the Prince of Wales wrote to Ferdinand that he was looking forward to seeing his fountain and ‘also the plan of the little garden near the Dairy wh you propose - & I hope you will be able to pay us a visit in Oct or Nov so as to talk matter[s] over' [32].

It is not known whether Baron Ferdinand, who died that winter, did actually make the visit. However, the garden in front of the dairy was laid out, posthumously, the following spring. Writing to his eldest sister the Dowager Empress Frederick, the Prince of Wales described in late February 1899 how he was busy laying out the garden ‘after poor Baron Ferdy's plan which I think will come out well' [33].

The fact that Baron Ferdinand supplied the Prince of Wales with such apparently detailed proposals for the garden at Sandringham, strongly suggests that he would have done the same for his own garden at Waddesdon. The design of the rose garden, the plan for the Aviary beds, the layout of the garden around the Dairy - these are all most likely by Baron Ferdinand himself.

There can be no doubt that the gardens at Waddesdon and Sandringham developed along similar lines during the last quarter of the 19th century, with extensive Pulham rockwork; extensive glasshouse complexes with orchids and Malmaison carnations; and dairies surrounded by small formal gardens (at Sandringham the cows were Danish, as one would expect, Princess Alexandra being Danish).

Both estates also featured rose gardens, Waddesdon's being one of the last additions to the garden by Ferdinand, while the one at Sandringham was laid out by the head gardener Archibald Mackellar in 1896. At Sandringham it was enclosed within wire treillage, with 1300 dwarf standard and climbing roses and a wire rose temple ‘dripping with roses' [34]. This is not dissimilar to the recently restored rose garden at Waddesdon Manor.

It was not only Queen Victoria's son who was much taken with Baron Ferdinand's gardening skills. Her eldest daughter, the Empress Frederick, was also impressed by his talents. Writing to her mother after a visit by Ferdinand to her house at Frederickshoff in 1894, she referred to him as ‘an excellent gardener and good botanist and [he] has a good deal of artistic knowledge and taste' [35]. On a return visit to Waddesdon, in 1897, she planted a tree near the stables to mark the Queen's golden jubilee. Unfortunately no trace of this survives.

Waddesdon accounts book, 1887

Benefactor and patron

Like all the Rothschilds, Baron Ferdinand was a great benefactor and supporter of various charities. One of these was the Gardeners' Royal Benevolent Institution (still going strong today under the name of Perennial), the treasurer of which was Harry Veitch of the famous Veitch Nurseries [36].

In 1887 Ferdinand stood as its President, an honorary appointment which no doubt served the Institution well in its fundraising efforts. At its annual fundraising dinner on 29 June that year, the Baron found himself at ‘The Albion' in Aldersgate Street, London, supported by friends like Sir Robert Peel and Christopher Sykes, and ‘a large company of horticulturists and their friends' [37].

In his speech, the Baron ‘asserted the superiority of British forced flowers and fruit over Continental ones'. He also sketched the ‘history of gardens, from Adam to Paxton, Moore, Turner, Philip Frost and Zadok Stevens'.

Moore, Turner, Frost and Stevens were all eminent professionals in the field of horticulture who had died in recent months. Ferdinand's speech might have been scripted, but it is quite possible that he was at least acquainted with these four men.

In the same fundraising speech he made a plea to his fellow garden owners to contribute to the charity, claiming that it was not right that ‘those who derived gratification from their gardens should forget the gardeners, to whom they owed so much' [38].

Baron Ferdinand also supported the Royal Horticultural Society, and is believed to have attended their shows regularly [39]. Although Ferdinand (and his sister Alice) provided many a prize for the annual shows put on by the Aylesbury Floral and Horticultural Society, neither he nor his head gardener appear to have entered any competitions themselves; they no doubt realised that the enormous advantages they had over the many other competitors would make for an uneven competition.

Baron Ferdinand proved to be a patron to individuals too. His main orchid supplier, Frederick Sander, was born in Germany in 1847 but, like Ferdinand, he had come over to England in about 1860 and settled there. It is tempting to speculate that the two men talked in their native tongue whenever they met.

The Waddesdon accounts show huge payments to Sander, not only for supplying orchids but also for the care and maintenance (painting) of the glasshouses in which they were grown. This suggests that Sander, whose main orchid nursery was in St Albans in Hertfordshire, might have had a kind of franchise at Waddesdon, although as the accounts indicate, Sander was by no means the only supplier of orchids to the Manor.

When Queen Victoria visited in 1890, it was Sander who was introduced to her by Baron Ferdinand, an honour apparently not bestowed upon his head gardener John Jaques. Shortly afterwards Sander was able to call himself Royal Orchid Grower.

Another royal introduction by Baron Ferdinand, which proved very successful, was that of Elie Lainé, his landscape gardener, to the Belgian King Leopold. In his ‘Red Book' Ferdinand describes how Lainé went on to undertake a number of important works for the Belgian king: 'These commissions [he] owed ....directly to me' [40]. Another commission Laîné might well have owed to Ferdinand, is that at Armainvillier, the estate of Ferdinand's cousin Edmond James (1845-1934).

Finally, the account books at Waddesdon suggest that there are a number of horticultural firms whose businesses must have derived enormous advantage from their Rothschild patronage.

These include the nurseries of Veitch, Anthony Waterer and Messrs. H. Lane & Sons of Berkhamsted, who all received substantial, regular payments throughout the 1880s and 1890s . As mentioned before, significant payments were also recorded on a regular basis to the firm of James Pulham & Son, for rockwork, and R. Halliday & Co. of Middleton near Manchester, manufacturer of glasshouses.

Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild died at Waddesdon of a heart attack on his birthday, 17 December 1898. His interest in horticulture and gardening was both productive and - luckily for posterity - long-lived. Today, visitors to Waddesdon can gain a sense of what his creation must have been, as a number of features from Ferdinand's day (previously lost due to changes in taste and practise) have been restored, most recently the flamboyant bedding arrangements of the Aviary garden.

Endnotes

- Reminiscences, p.32-33

- Reminiscences, p.21

- Reminiscences, p.21

- Reminiscences, p.33

- Reminiscences, p.33

- Reminiscences, p.34

- Prevost-Marcilhacy, p. 350

- Reminiscences, p.54

- Letter from Evelina, 19 September 1865

- Letter to Lionel Rothschild, 2 February 1875

- Red Book, p.10

- The Woman at Home, p110

- Elliot

- The Woman at Home

- Bucks Advertiser, 23 July 1881

- Red Book, p.4

- Gardener’s Chronicle, 27 June 1885, p820-2

- Bucks Advertiser, 6 August 1887

- Letter to the 5th Earl of Rosebery, 26 December 1886

- Gardener’s Chronicle, 24 December 1898

- Vincent, p.49

- Country Life, 20 Aug 1898, p208

- Letter at Rothschild Archives ref. 000/26/RFamC8 – n.d.

- Gardener’s Chronicle, 27 June 1885, p821

- Sander, p.47

- Miriam Rothschild, p.176

- Letter (20 Aug 1891), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 20.2004

- Letter (31 July [1891]), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 19.2004

- Letter (26 Aug 1891), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 21.2004

- Letter (30 July [1891]), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc.18.2004

- Letter (13 Oct 1898), at The Royal Archives ref. RA GV/CC 6/53. Reproduced by kind permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Archibald Mackellar, previously head gardener to the Duke of Roxburgh at Floors Castle, was head gardener at Sandringham in the 1890s.

- Letter (26 September 1898) at Waddesdon Manor ref acc. 35.2004

- Letter (26 Feb 1899), at The Royal Archives ref. RA VIC/Add A4/99. Reproduced by kind permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

- Strong, p.131

- Ramm, p.170

- The Gardeners’ Royal Benevolent Institution was one of a number of Victorian horticultural charities; another popular charity was the Royal Gardeners’ Orphan Fund. In 1887 it was reported that the Rothschilds had donated over £600 to Gardeners’ Royal Benevolent Institution over the previous 15 years.

- A full report of the meeting appeared in Gardener's Chronicle (2 July 1887) pp18-19; see also Ferdinand’s obituary in Gardener's Chronicle (24 Dec 1898) pp457-8; and The Gardening World (9 July 1887) pp707-8

- Gardeners’ Chronicle (24 Dec 1898) p458

- Royal Horticultural Proceedings, 1888

- Red Book, p.10

Sources

Bellaigue, Geoffrey de. Notes (Waddesdon Accounts held at Rothschild Archives at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. no. 3593).

Banbury Guardian (24 Dec 1898).

Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News (23 July 1881).

Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News (21 July 1883).

Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News (6 Aug 1887).

Country Life (20 Aug 1898) p208.

Davis, R. W., 'Rothschild, Ferdinand James Anselm de, Baron de Rothschild in the nobility of the Austrian empire (1839–1898).' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. 4 Mar. 2009.

Elliott, Brent, Waddesdon Manor. The Garden (National Trust, 1994).

Gardener's Chronicle (27 June 1885) p821.

Gardener's Chronicle vol 25 n.s. (19 June 1886).

Gardener's Chronicle (2 July 1887).

Gardener's Chronicle (24 Dec 1898) pp457-8.

Gardener's Chronicle (24 Dec 1898) p458.

Gardening World (9 July 1887) pp707-8.

Halliday, R., ‘Ground Plan and Hothouses etc. Waddesdon Manor’ (c.1880s; private collection; copy at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc.70).

Halliday, R., ‘Fruithouses Waddesdon Manor’ (c.1880s; private collection; copy at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 75).

Halliday, R., ‘Glass corridor etc. For Baron F. de Rothschild’ (1884; private collection; copy at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 76).

Jewish Chronicle (3 Aug 1900) pp18-19.

Midland Daily Telegraph Coventry (19 Dec 1898).

Plant list (1884), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc.403.

Pons, Bruno, Waddesdon Manor. Architecture and Panelling (London: Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd, 1996).

Prevost-Marcilhacy, Pauline, Les Rothschild bâtisseurs et mécènes (Paris: Flammarion, 1995).

Letter, Rothschild Archives ref. 000/26/RFamC8 – n.d.

Prince of Wales, Letter (30 July [1891]), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc.18.2004; Letter (31 July [1891]), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 19.2004; Letter (20 Aug 1891), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 20.2004; Letter (26 Aug 1891), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 21.2004; Letter (26 Sept 1898), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 35.200.

Letter (13 Oct 1898), at The Royal Archives ref. RA GV/CC 6/53.

Letter (26 Feb 1899), at The Royal Archives ref. RA VIC/Add A4/99.

Rothschild, Evelina de, Letters, Rothschild Archive ref. RAL 000/23. The letters are also accessible on the Rothschild Research Forum website.

Rothschild, Ferdinand de, Letter to his uncle Lionel Rothschild (2 Feb 1875), at Rothschild Archives ref. XI/109/118/RfamC8.

Rothschild, Ferdinand de, Letters to 5th Earl of Rosebery (26 Dec 1886). Copies at Waddesdon Manor library.

Rothschild,Ferdinand de, ‘Red Book’ (1897), at Waddesdon Manor ref. acc. 54 and acc. 938 (transcript); also accessible on the Rothschild Research Forum website.

Rothschild, Ferdinand de, ‘Reminiscences’, 1897 (Waddesdon Archives ref. acc. 177.1997).

Rothschild, Miriam et al. The Rothschild Gardens (London: Gaia Books Ltd, 1996) p176.

Royal Horticultural Society Proceedings (1888) vol. 11 (n.s.) p.xviii.

Sander, Frederick, Reichenbachia. Orchids illustrated and described (second series) Vol 1 (1892, London) p47.

Strong, Sir Roy, Victorian Gardens (London: BBC Books and Conran Octopus Ltd, 1992) pp128-137.

Vincent , John (ed) The Crawford Papers (1984, Manchester University press, Manchester) p49.

Woman at Home, ‘Two Rothschild Homes’ (undated - possibly late 1890s) p110. Copy at Waddesdon Archives, ref. acc. 223.